Harv's Norman supercharger thread

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

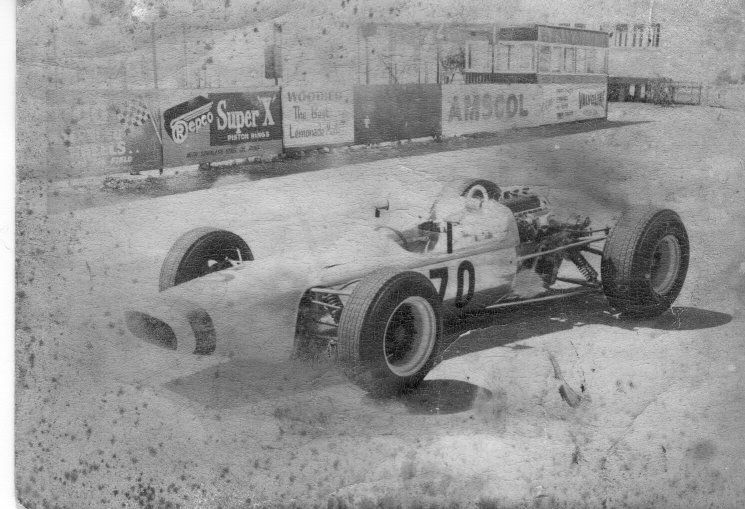

I got reminded by Mike that this year marks the 51st anniversary of the Norman supercharged Elfin, operated by Andrew Mustard and Mike McInerney setting the following Australian national records:

• the flying start kilometre record (16.21s, 138mph),

• the flying start mile record (26.32s, 137mph), and

• the standing start mile record (34.03s, 106mph).

The vehicle falls into the FIA Category A Group I class 6, with the record set at Salisbury, South Australia on October 11th, 1964. These records stand in perpetuity (i.e. they can no longer be challenged under CAMS rules).

This October long weekend also marks the 50th anniversary of Mike’s attempt (in twin-Norman supercharged guise) to pursue the standing ¼ mile, standing 400m and flying kilometre records (October 1965). Sadly, the twin-Norman supercharged Elfin no longer holds those records, as the ¼ mile and flying kilometre (together with a few more records) were set at this time by Alex Smith in a Valano Special.

Happy Golden Jubilee, Mr McInerney.

Regards,

Harv

• the flying start kilometre record (16.21s, 138mph),

• the flying start mile record (26.32s, 137mph), and

• the standing start mile record (34.03s, 106mph).

The vehicle falls into the FIA Category A Group I class 6, with the record set at Salisbury, South Australia on October 11th, 1964. These records stand in perpetuity (i.e. they can no longer be challenged under CAMS rules).

This October long weekend also marks the 50th anniversary of Mike’s attempt (in twin-Norman supercharged guise) to pursue the standing ¼ mile, standing 400m and flying kilometre records (October 1965). Sadly, the twin-Norman supercharged Elfin no longer holds those records, as the ¼ mile and flying kilometre (together with a few more records) were set at this time by Alex Smith in a Valano Special.

Happy Golden Jubilee, Mr McInerney.

Regards,

Harv

327 Chev EK wagon, original EK ute for Number 1 Daughter, an FB sedan meth monster project and a BB/MD grey motored FED.

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

327 Chev EK wagon, original EK ute for Number 1 Daughter, an FB sedan meth monster project and a BB/MD grey motored FED.

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

Ladies and gents,

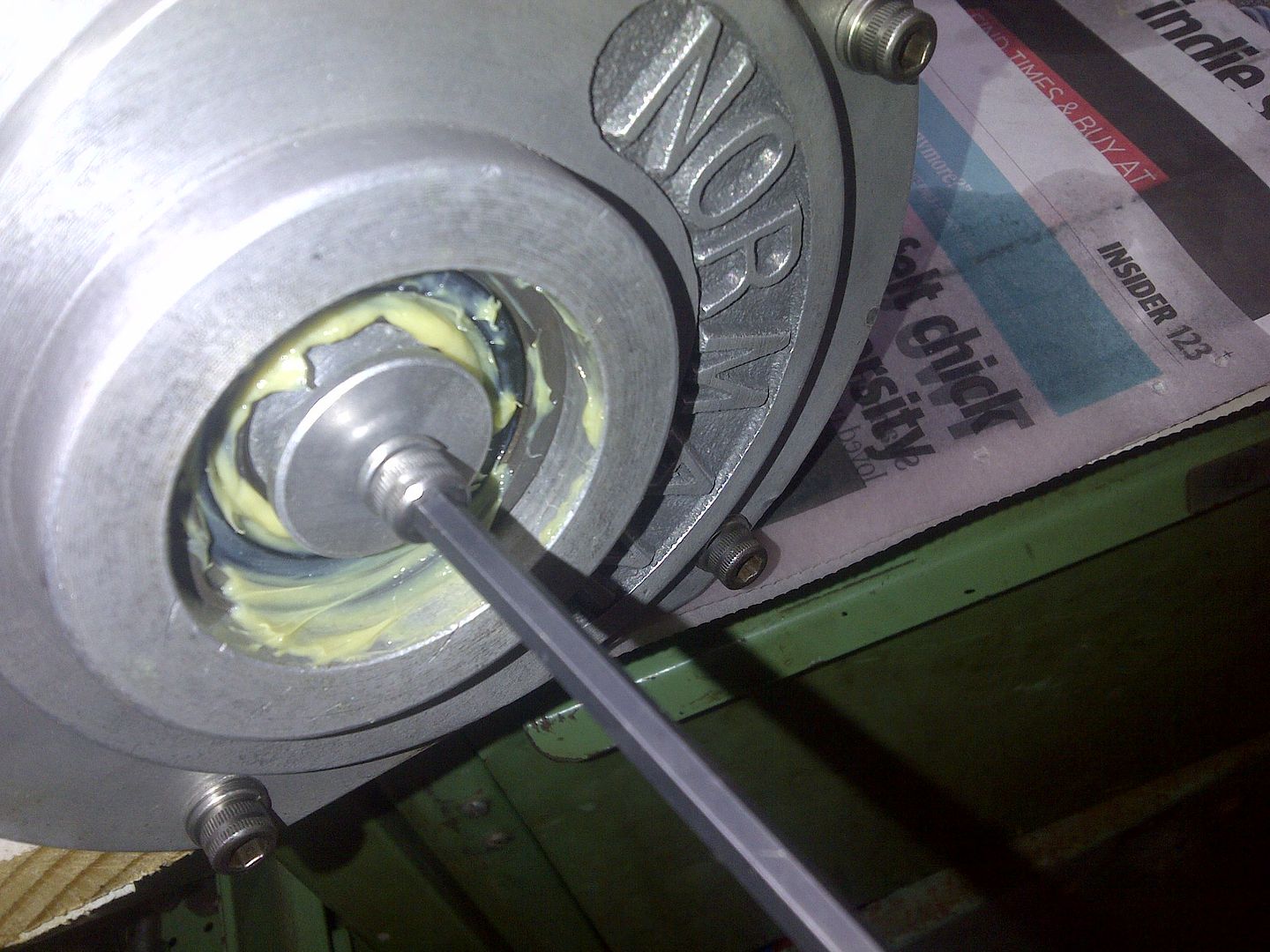

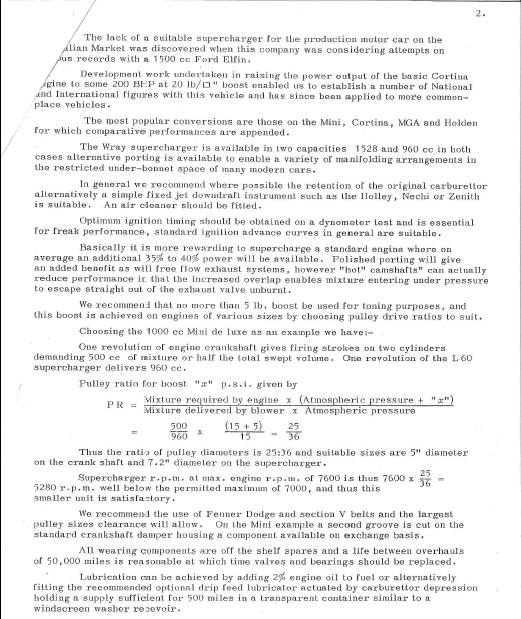

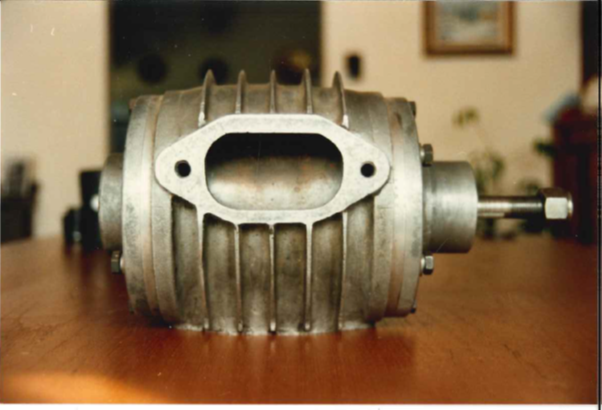

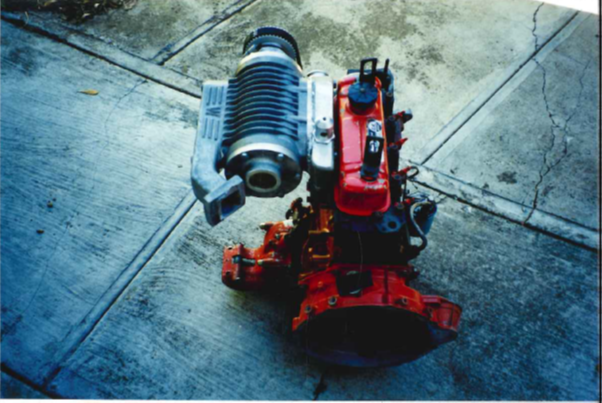

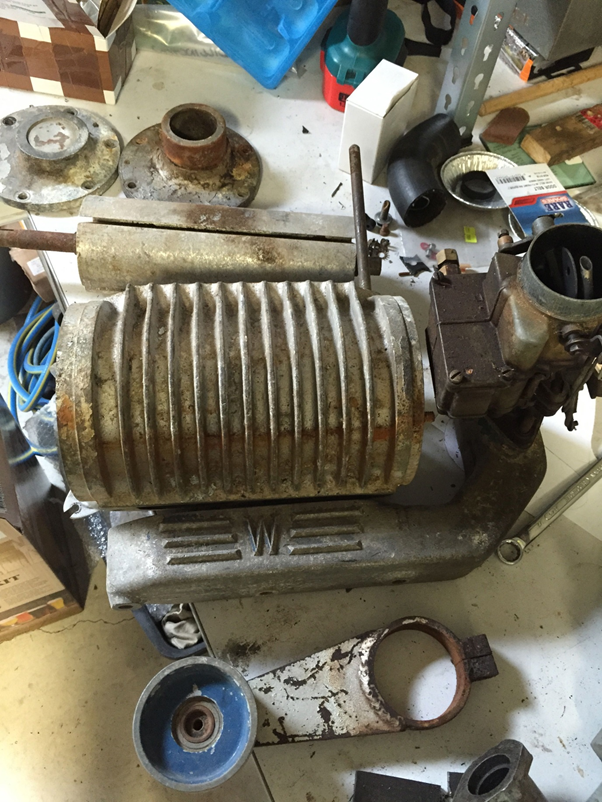

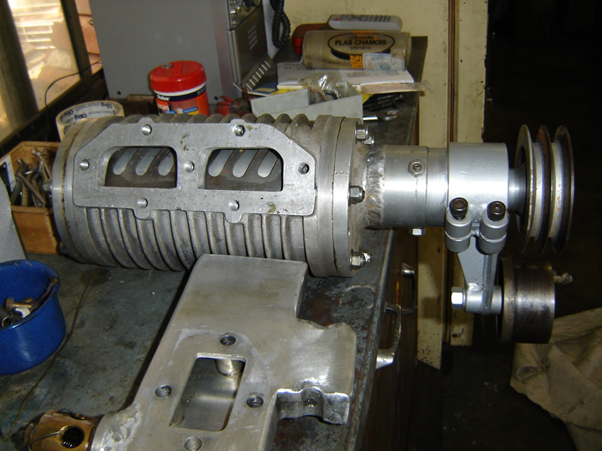

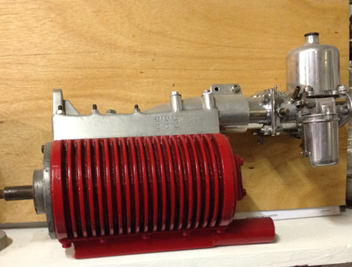

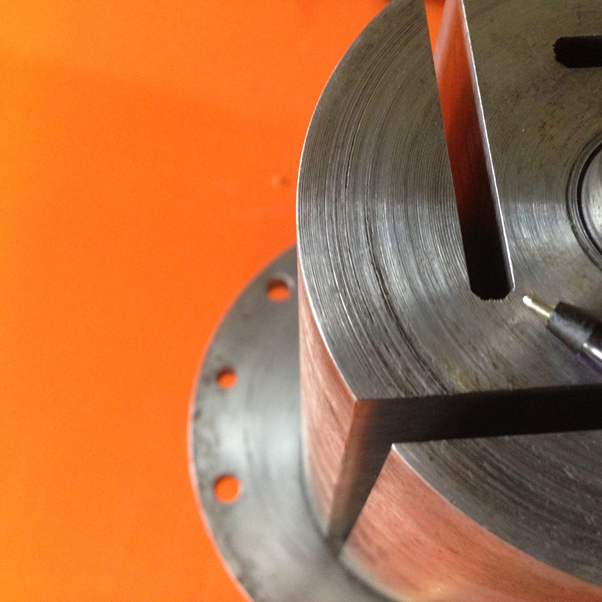

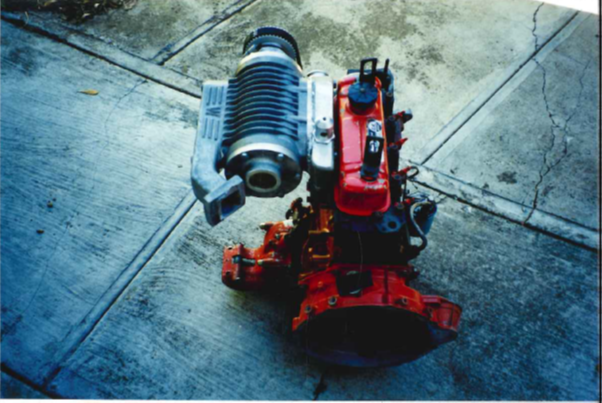

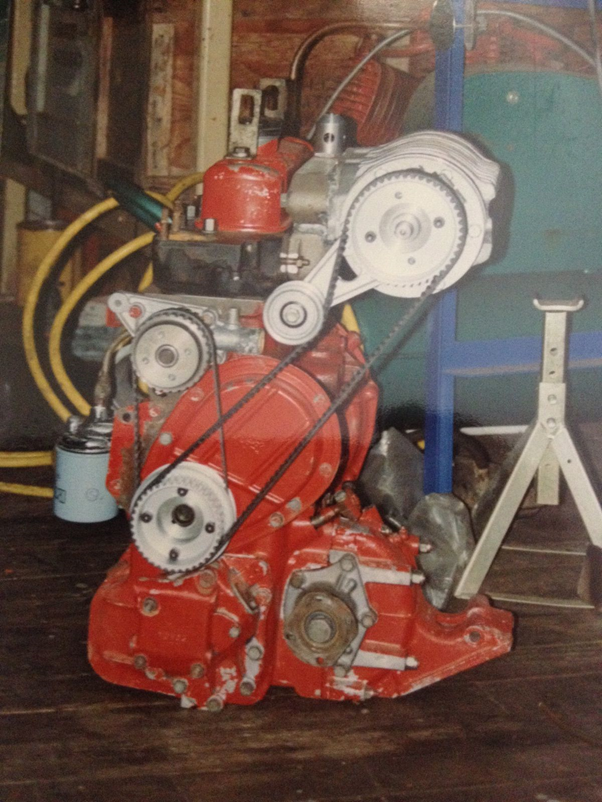

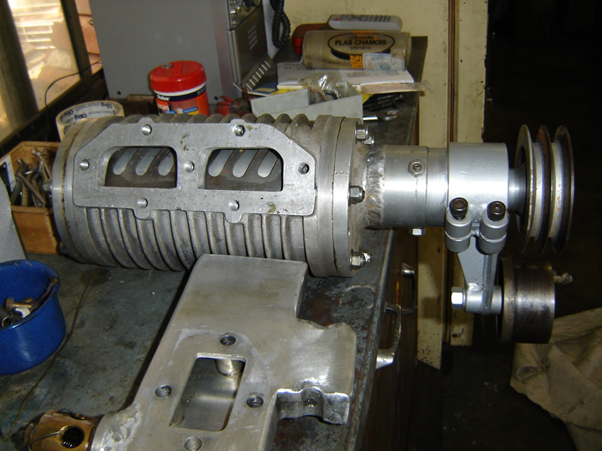

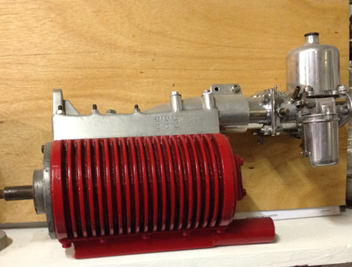

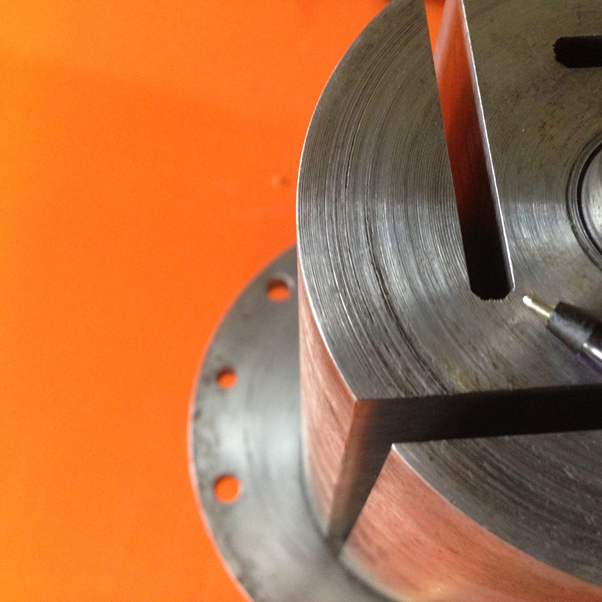

This post has some photos of the overhaul I recently completed for Gary’s 350 Norman.

The Norman was originally running a suck-through 2” SU on some form of cross-flow four cylinder engine… probably BMW. It’s been stripped down and rebuilt. Overall in excellent shape, though the vanes showed delamination and were replaced with new F57 ones, and one vane spring had fractured (all vane springs replaced with Inconel). I understand this one is going back into storage for the time being… if one of you guys distracts Gary long enough, I’ll bolt it to a red motor

There were quite a few learnings along the way, some of which I’ve posted here. I’ll comb through the notes I wrote for Gary and post a few more of the learnings over the next week or so.

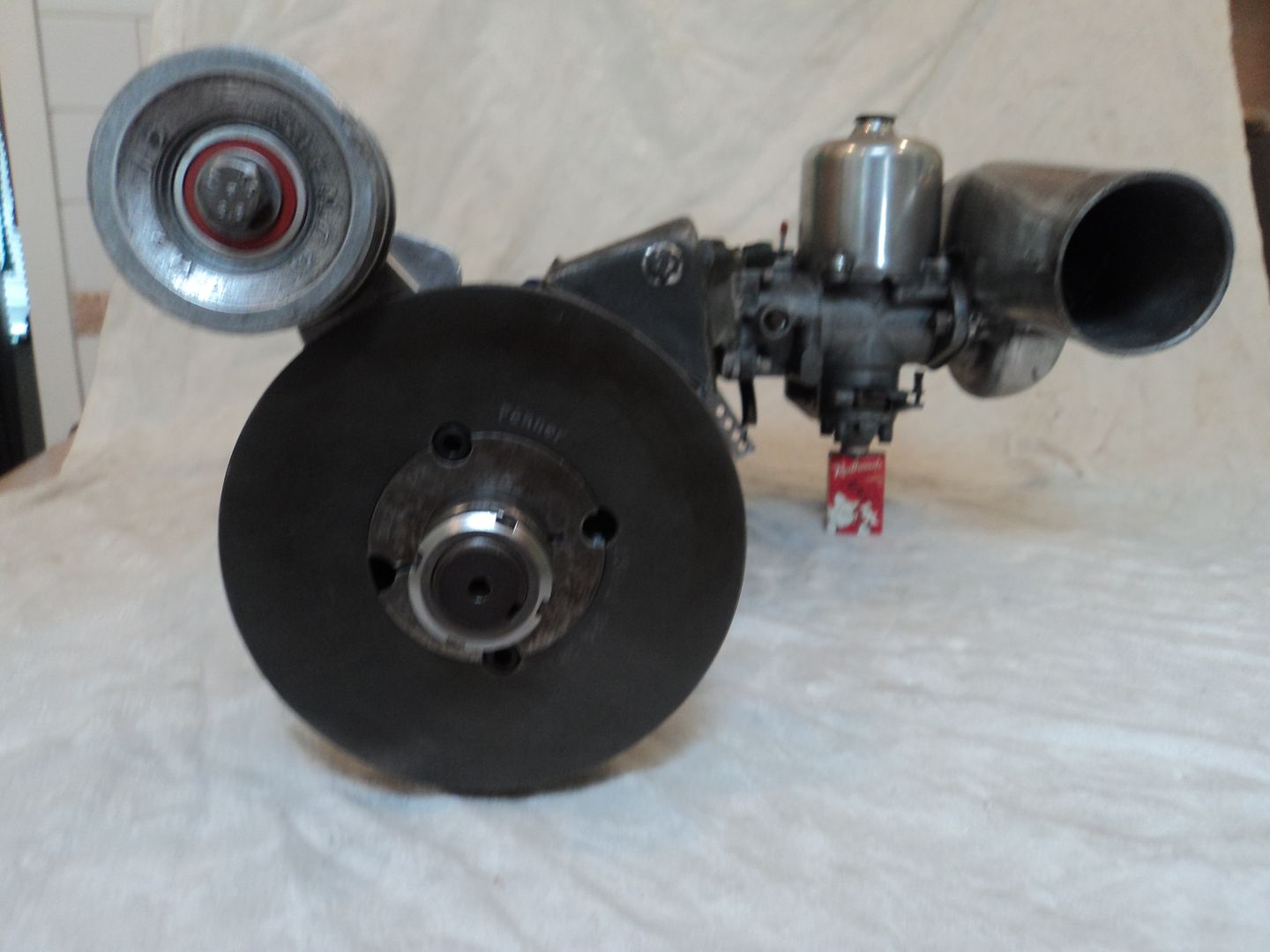

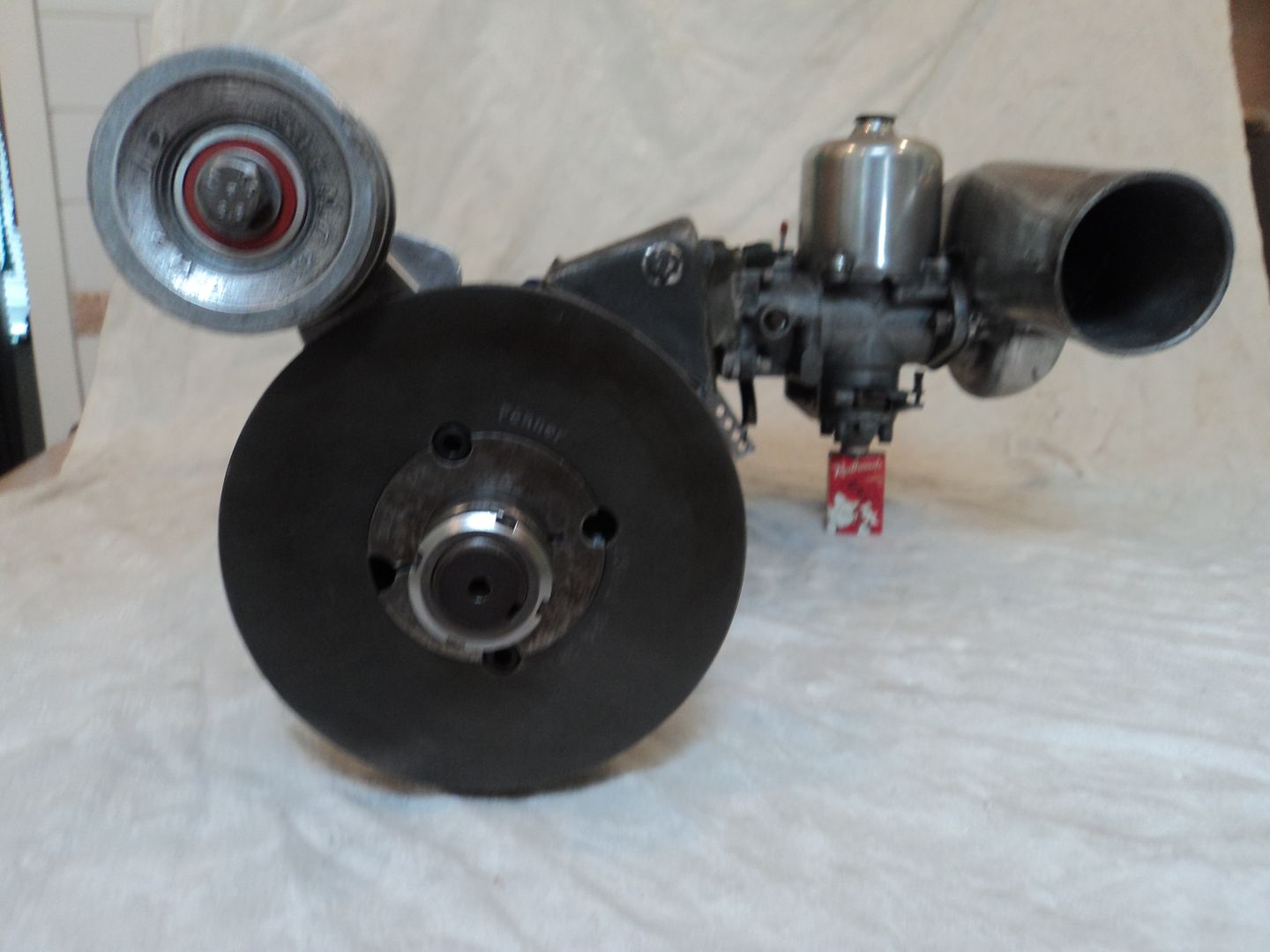

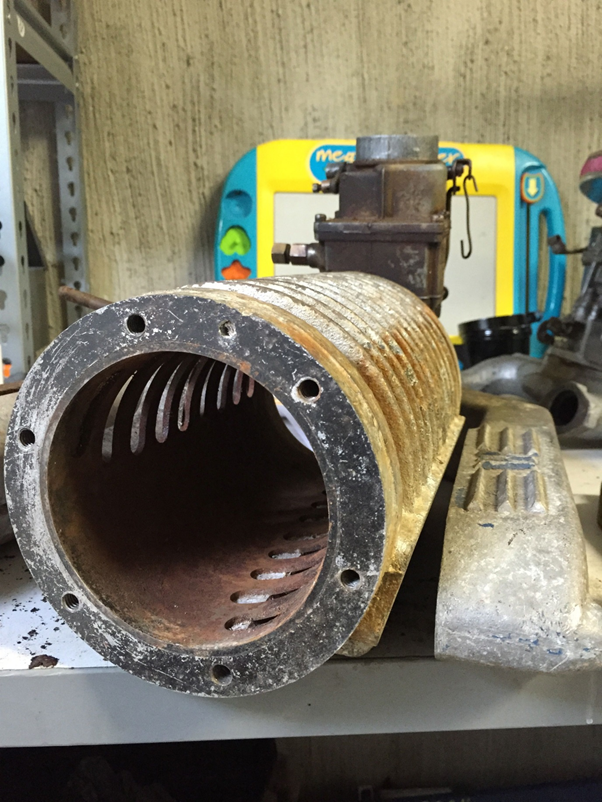

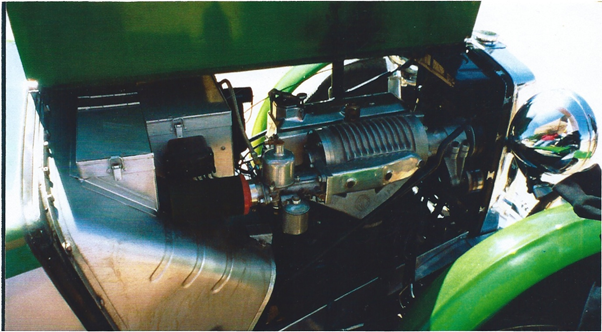

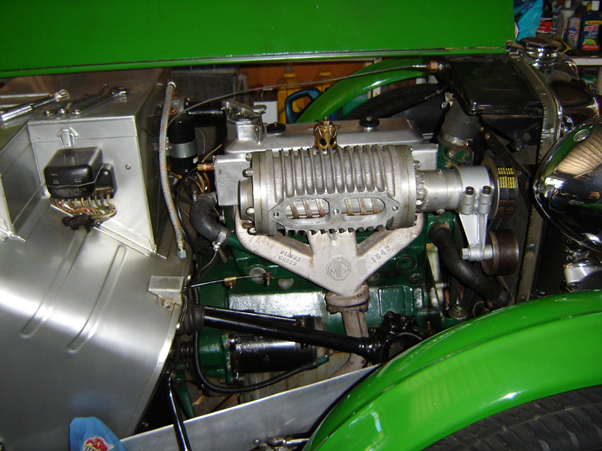

Cold air intake… big enough to swallow a pigeon:

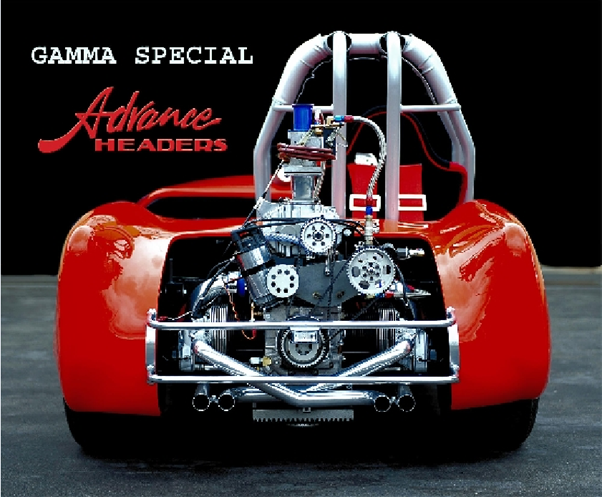

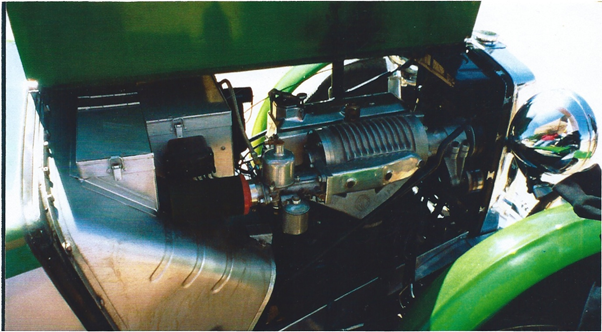

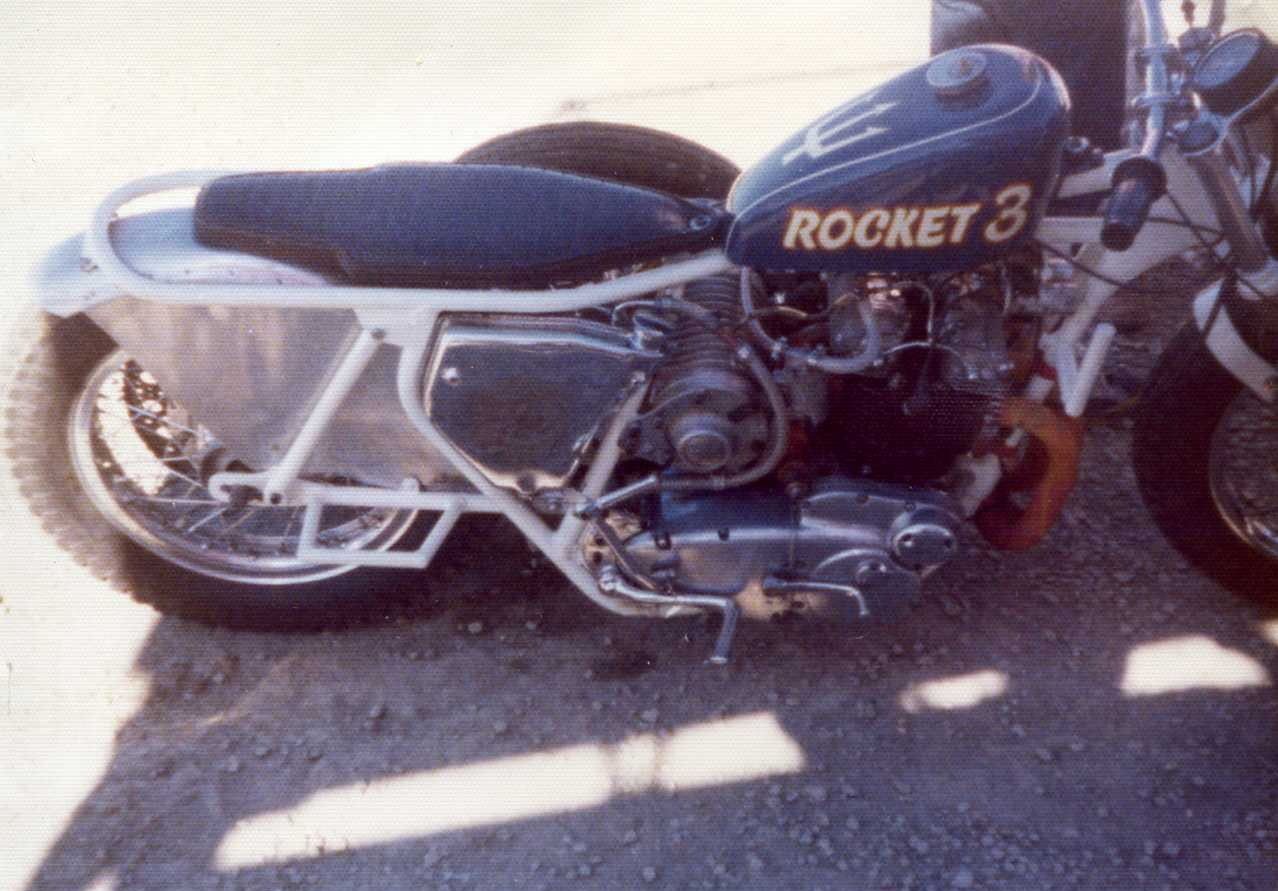

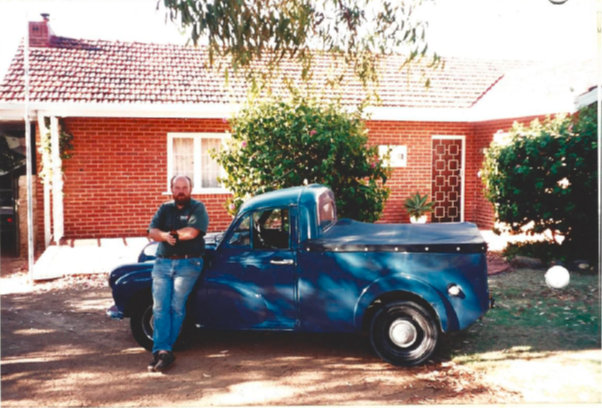

Mad Max meets Mike Norman… if you see this in your rear view mirror, be afraid… very afraid:

Cheers,

Harv (deputy apprentice Norman supercharger fiddler)

This post has some photos of the overhaul I recently completed for Gary’s 350 Norman.

The Norman was originally running a suck-through 2” SU on some form of cross-flow four cylinder engine… probably BMW. It’s been stripped down and rebuilt. Overall in excellent shape, though the vanes showed delamination and were replaced with new F57 ones, and one vane spring had fractured (all vane springs replaced with Inconel). I understand this one is going back into storage for the time being… if one of you guys distracts Gary long enough, I’ll bolt it to a red motor

There were quite a few learnings along the way, some of which I’ve posted here. I’ll comb through the notes I wrote for Gary and post a few more of the learnings over the next week or so.

Cold air intake… big enough to swallow a pigeon:

Mad Max meets Mike Norman… if you see this in your rear view mirror, be afraid… very afraid:

Cheers,

Harv (deputy apprentice Norman supercharger fiddler)

327 Chev EK wagon, original EK ute for Number 1 Daughter, an FB sedan meth monster project and a BB/MD grey motored FED.

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

Ladies and Gents,

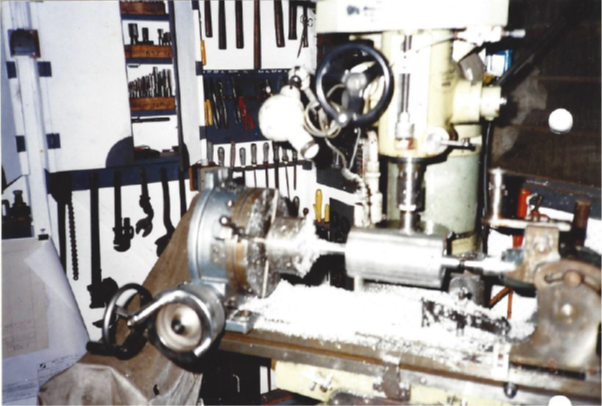

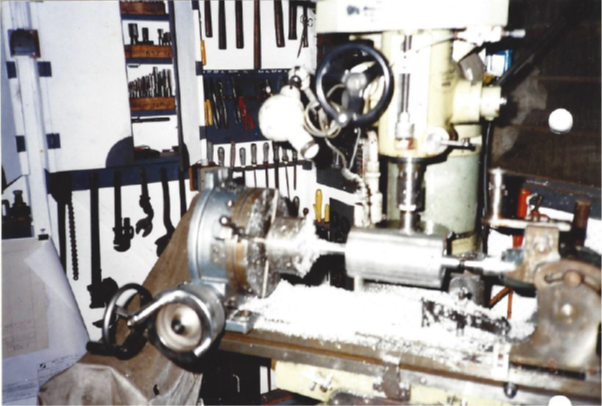

As I was overhauling Gary’s 350 Norman, I took detailed notes and photos to send to him. I’ve finally had some time to trawl back through my notes and pull out some of the learnings. The post below covers them, albeit in no particular order.

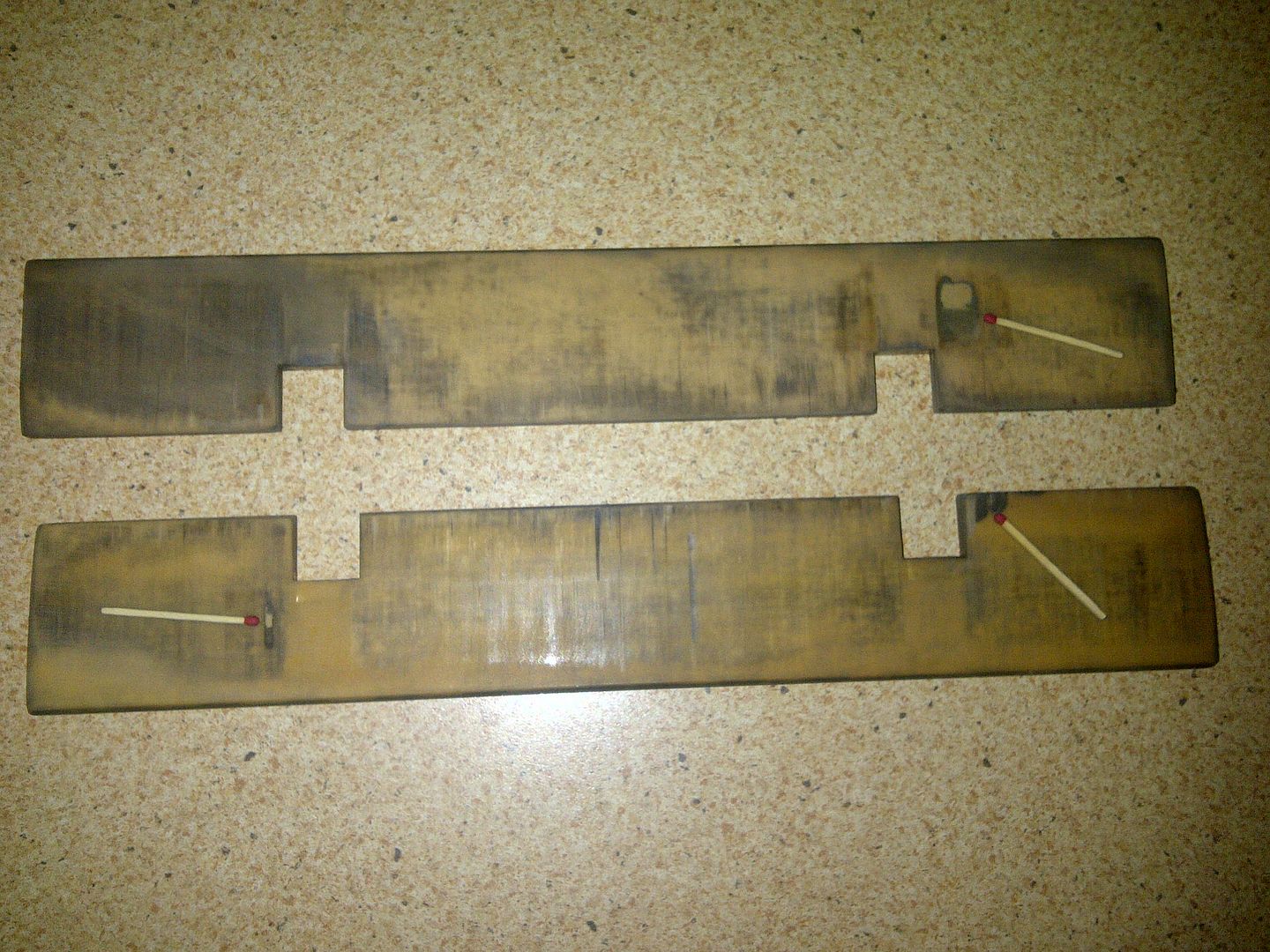

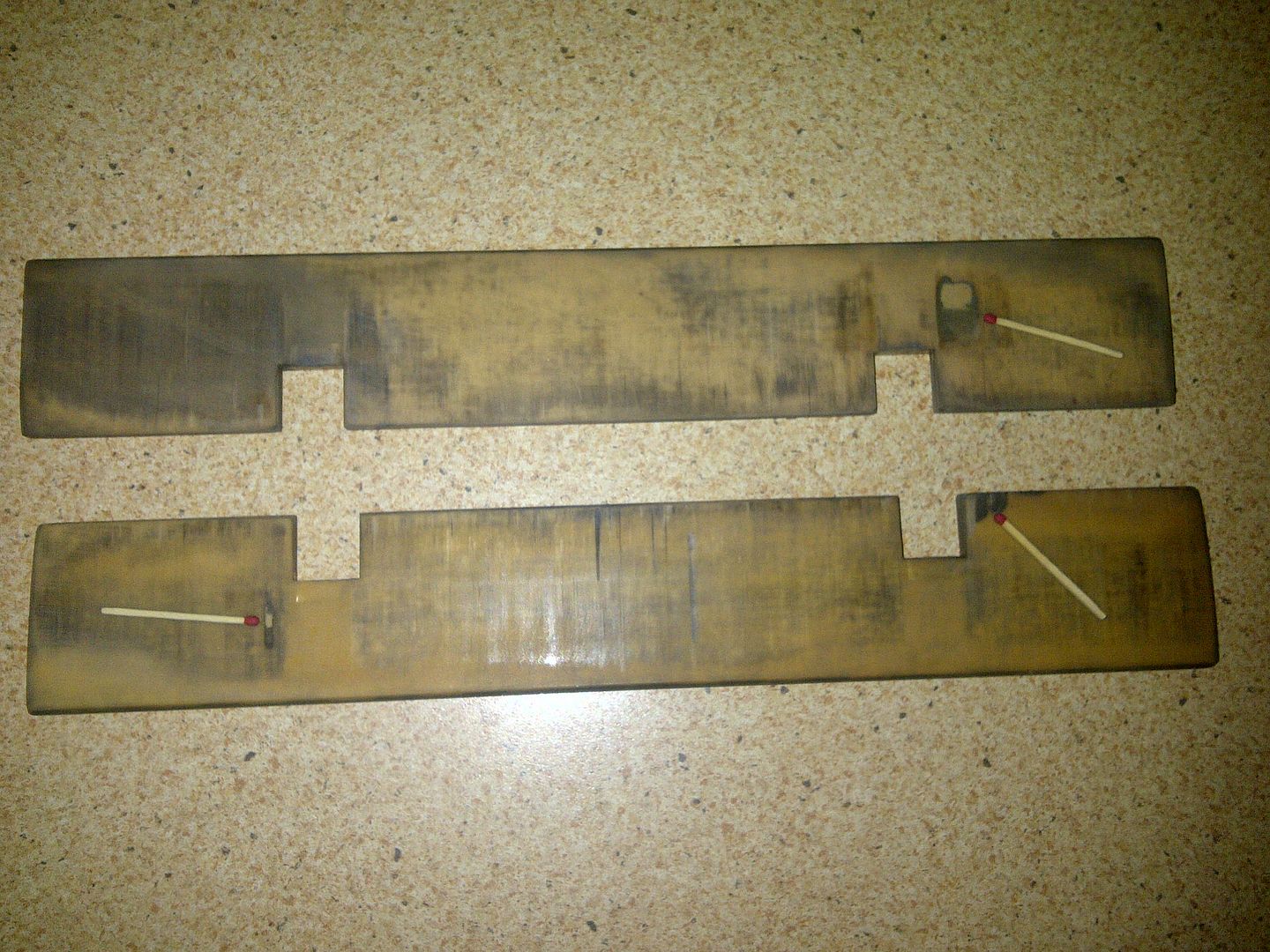

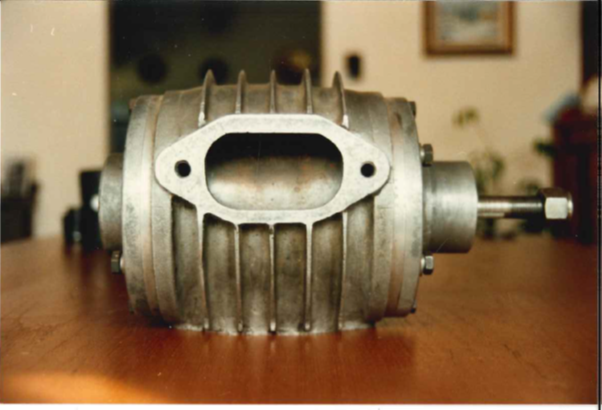

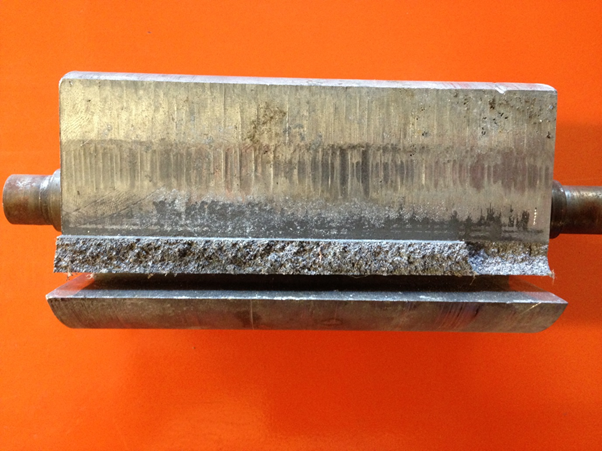

When the original vanes were pulled from the Norman, it was apparent that they had started to suffer from delamination. The photo below shows two of the vanes, with the delaminations highlighted by the match heads.

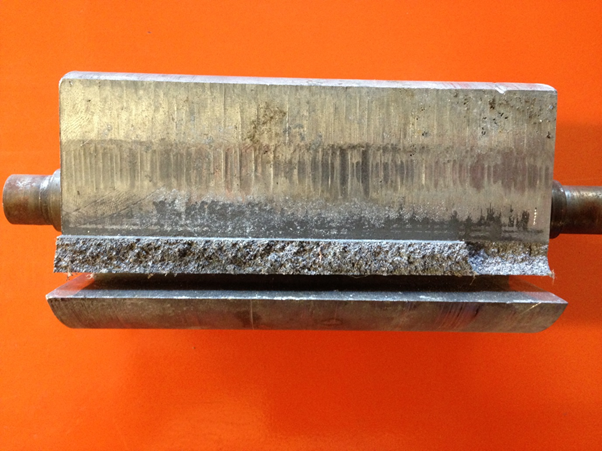

For replacement vanes, I got hold of some F57 (a Bakelite replacement which we have discussed before). The photo below (from top to bottom) shows the original Norman vane, an F57 vane cut to size, the F57 vane blank and a Bakelite vane blank.

Note that I now have a stockpile of both F57 and Bakelite vane blanks. They are large enough that they will suit all Normans, with the exception of the Type 270, Type 265 and perhaps Type 90 (never had one of these three apart). If anyone wants some, give me a yell. I also have the replacement Inconel valve springs that prevent spring shattering.

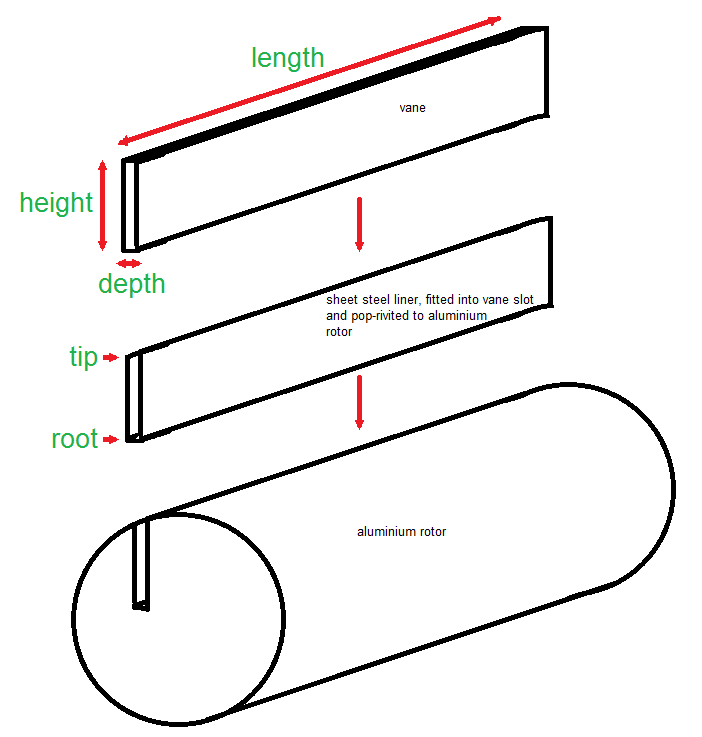

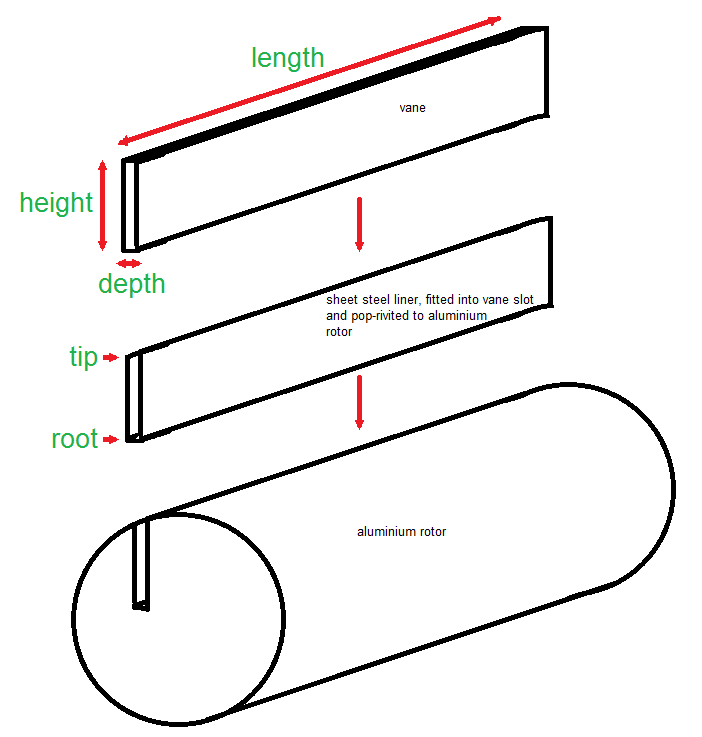

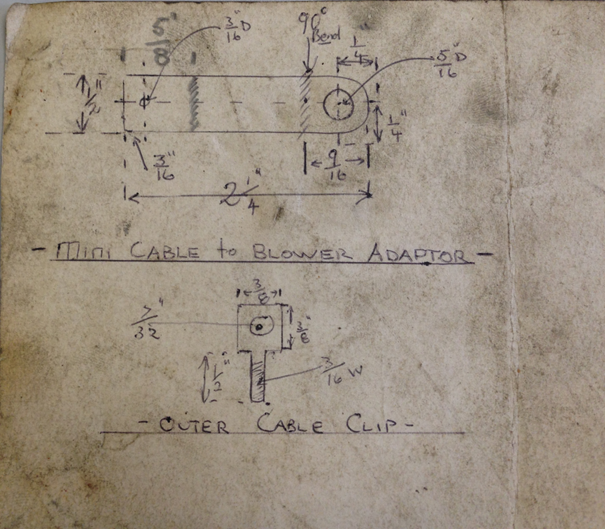

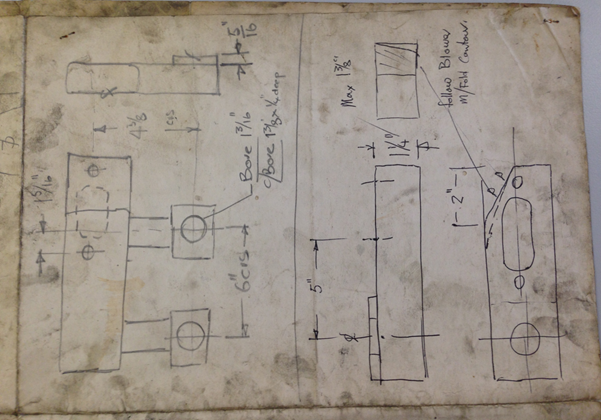

I started by cutting them the F57 blank length (see diagram), going slightly oversized.

This is a short length of cut, and easy to do with a hacksaw. The length needs to be then lapped down so that the vanes are exactly as long as the rotor. I held off lapping until the vanes were trimmed for depth. The next cut I needed to make was for height. This is a looooong cut, and a hacksaw would give a very wobbly finish. This needs to be fairly straight, as it provides a flat scraping/sealing surface against the casing wall. To do this, I put the angle grinder into a drop-saw jig, and set up a fence to run the vane along. This gives a nice, parallel and neat cut.

The final "cut" I needed to make was for depth. This is done by lapping the vanes down on lapping plates, aiming for a flop fit in the rotor. I’ve made up the lapping tool to do so (see drawing) out of some angle iron.

The superchargers made by Mike Norman have steel liners pressed into the vane slots and riveted in place. Interestingly (…maybe frustratingly), the resultant vane liner slot is nowhere near parallel. The root of the slot is narrower, whilst the drive end overall depth is narrower than the non-drive end. This makes the lapping a fun process – as the vane is rubbed against the lapping plate, you need to bear down slightly harder on the areas that need to be less deep. I was lapping with 80 grit paper, and spent quite some time on just one vane – the Kevlar reinforcing is softer than the sandpaper, but still resistant to being abraded. In the end, I went back to P40 paper, then smoothed out with finer grades.

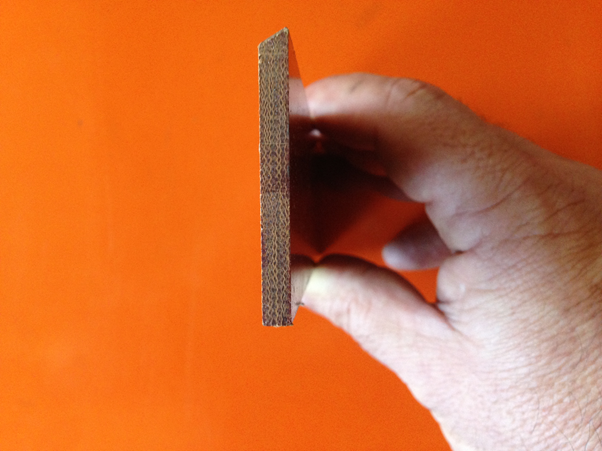

Having got the vanes sized correctly, I lapped down the length dimension - fit to rotor, check how much the vane hangs out, lap it down, repeat... a lot. With the dimensions finalised, I cut the spring notches and ground the relief grooves on the back of all three, using a diegrinder then flat file. The relief grooves are oriented on the downstream (low pressure) side of the vane. This configuration allows the vane slot root to vent. As the vanes operate in an oil film, there is a chance that the vanes form a seal in the vane slot, and either draw a vacuum at the vane root when sliding out, or build pressure at the vane root when sliding in. The grooves allow the vane root to vent, preventing the vane sealing with oil and not being able to rise/fall in the vane slot. An alternative way would have been to machine the relief grooves on the upstream (high pressure) side of the vane. The theory in that type of location is that higher pressure air/fuel can get under the vane and lift it, increasing vane seating pressure and getting a better seal. I have not seen this configuration put into place in Norman superchargers, but have heard of it being done for some Wray superchargers. The finished vanes are shown in the image below, along with the original Norman vanes.

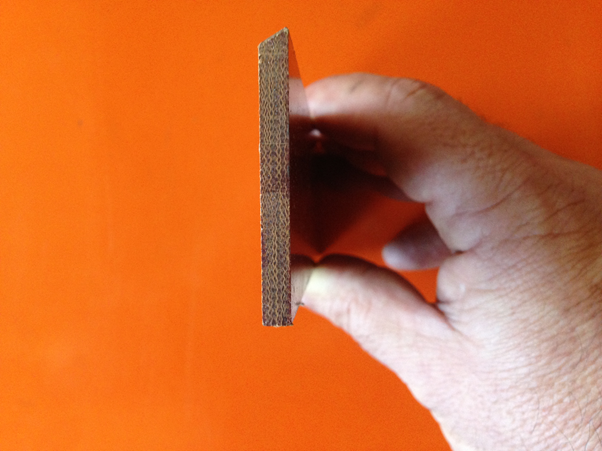

Another lesson learnt on the 350 Norman relates to the end-plate gaskets. None of the Normans made by Mike Norman that I have pulled apart have had these gaskets (whilst Eldred’d did). The gaskets seal the end plates to the casing. They also provide a means of setting non-drive end clearance, by varying gasket thickness. In the case of Gary’s 250 Norman, the non-drive end clearance was sufficient that gasekts were not required to increase clearance. To seal the end plates to the casing, I used a thin bead of sealant in the groove that exists for exactly that purpose (even if we used gaskets, I would still add the sealant). This is very different to Eldred’s Normans, which have no groove and needs some form of gasket to seal. I used a fine bead of Permatex Ultra Black sealant in the sealing groove. This is a highly flexible oil resistant sealant, good for up to 260°C (intermittent) service.

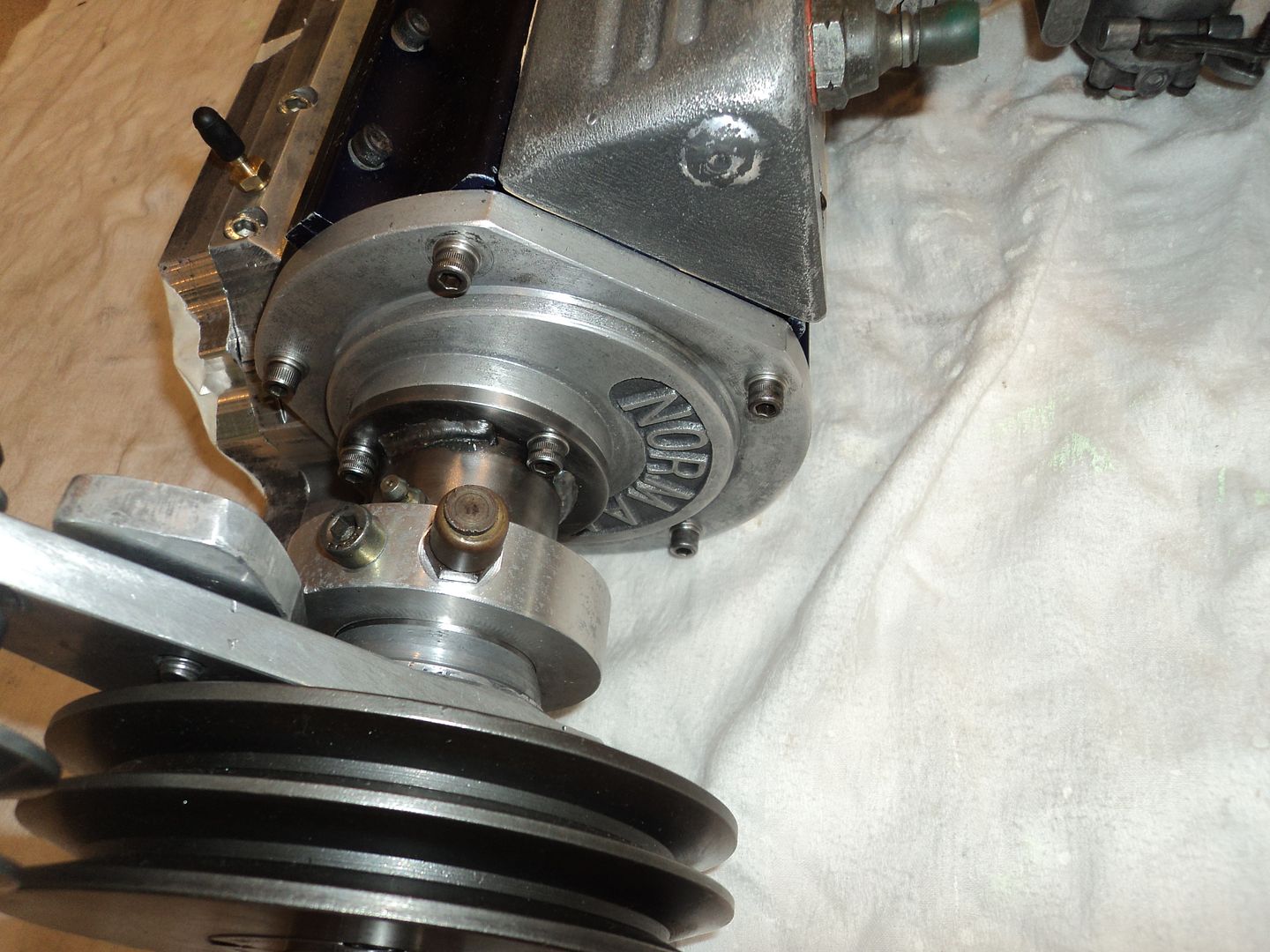

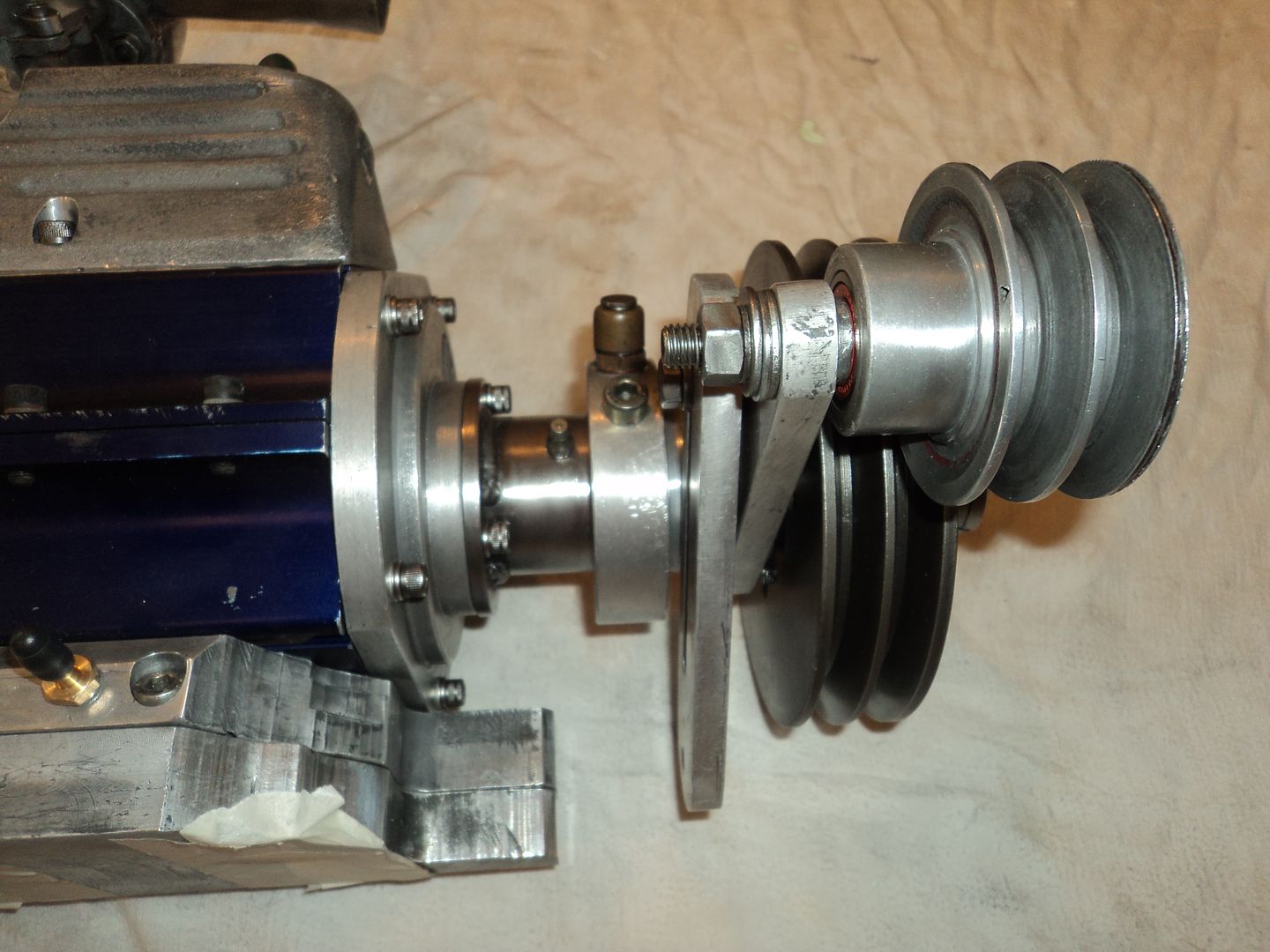

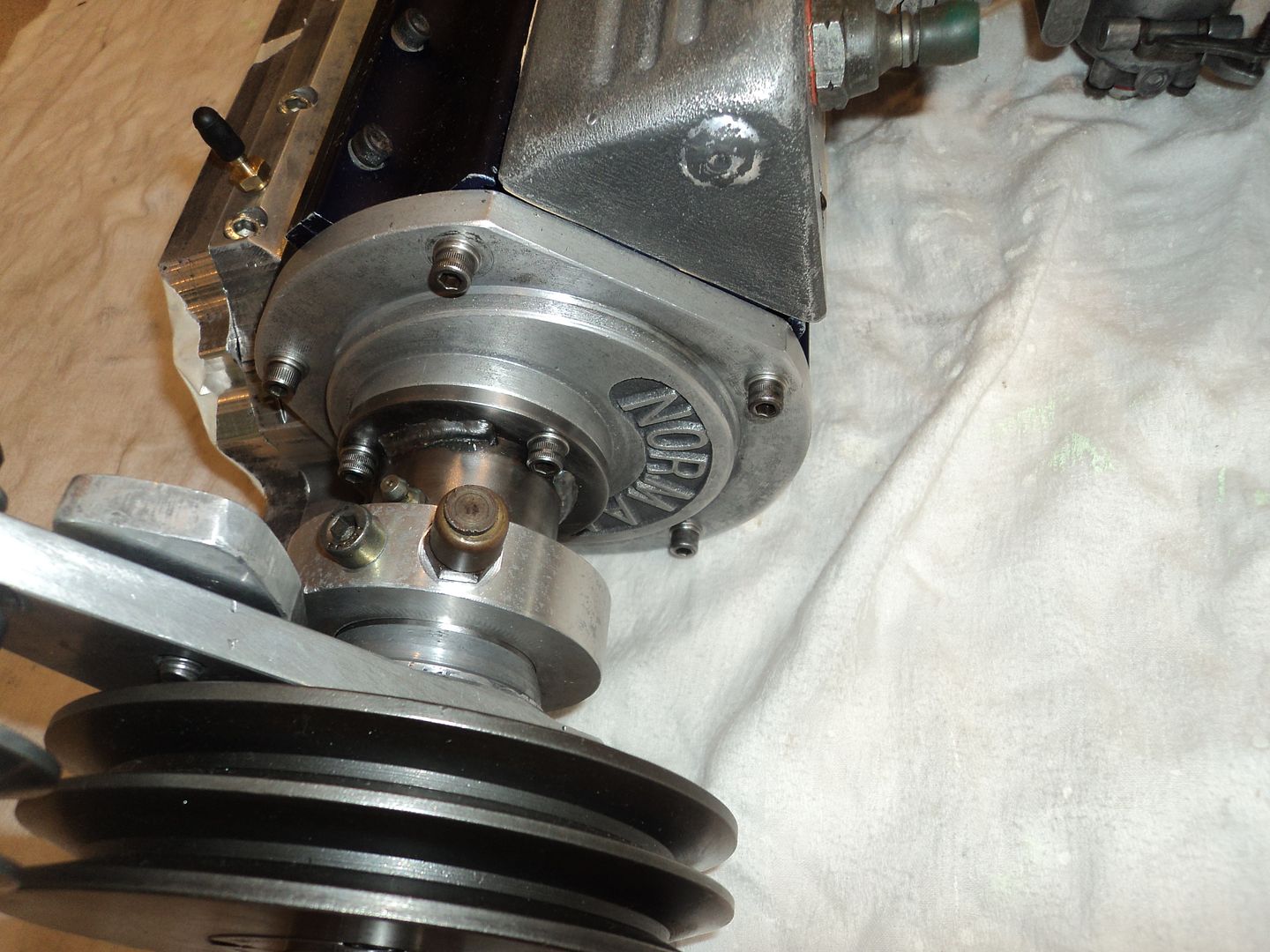

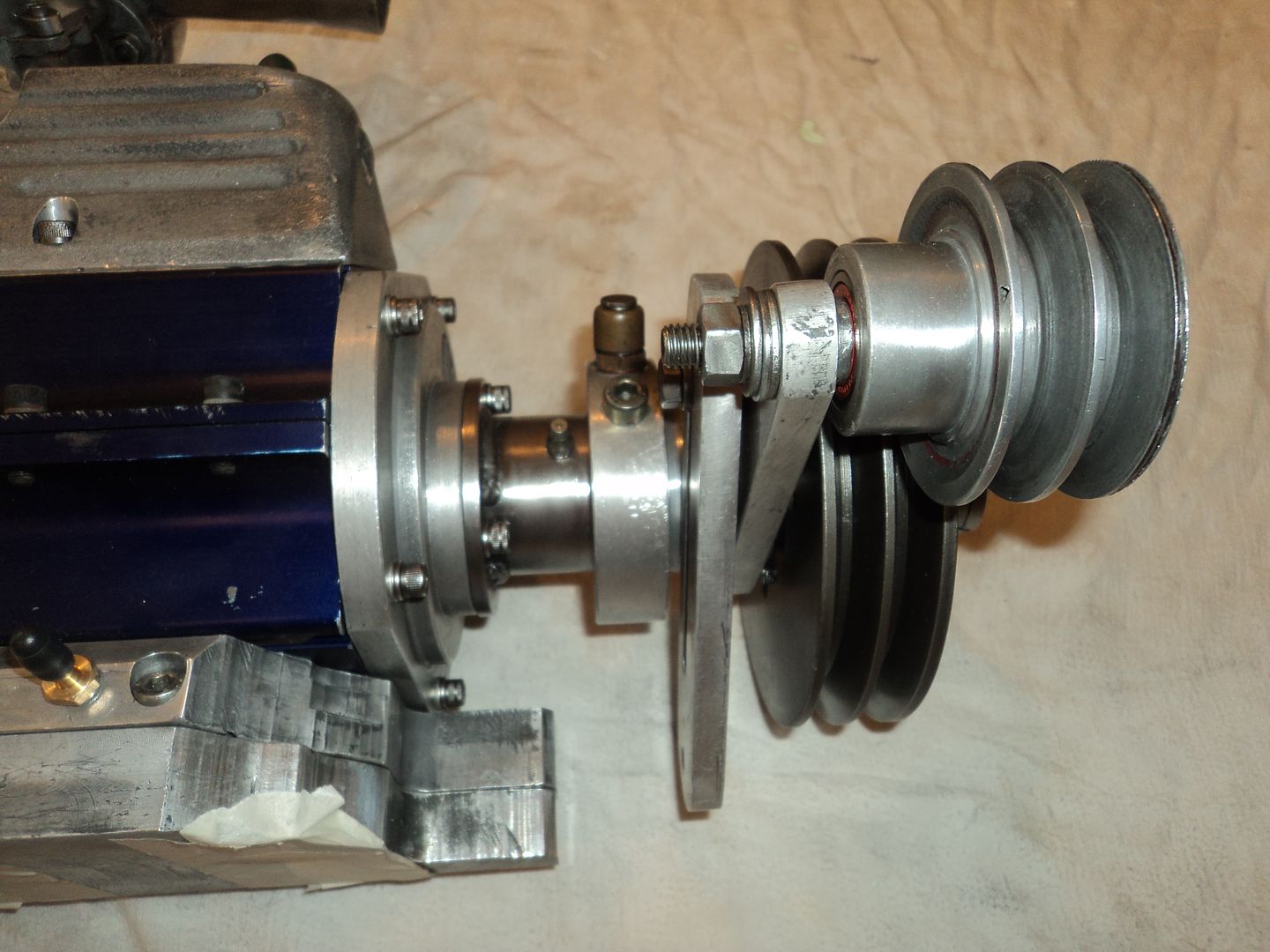

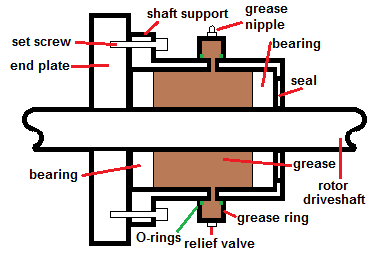

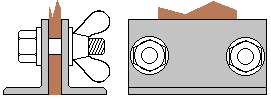

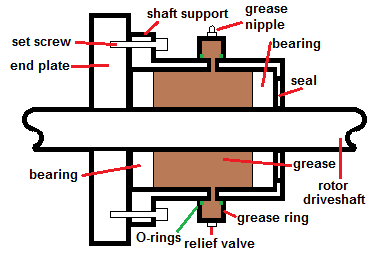

In some of Mike’s Normans a long drive shaft was ordered by the customer. This allows the supercharger to be mounted further back along the engine and still line up with the crank pulley. The longer drive shafts were fitted with a support assembly, indicated by the arrow in the diagram below:

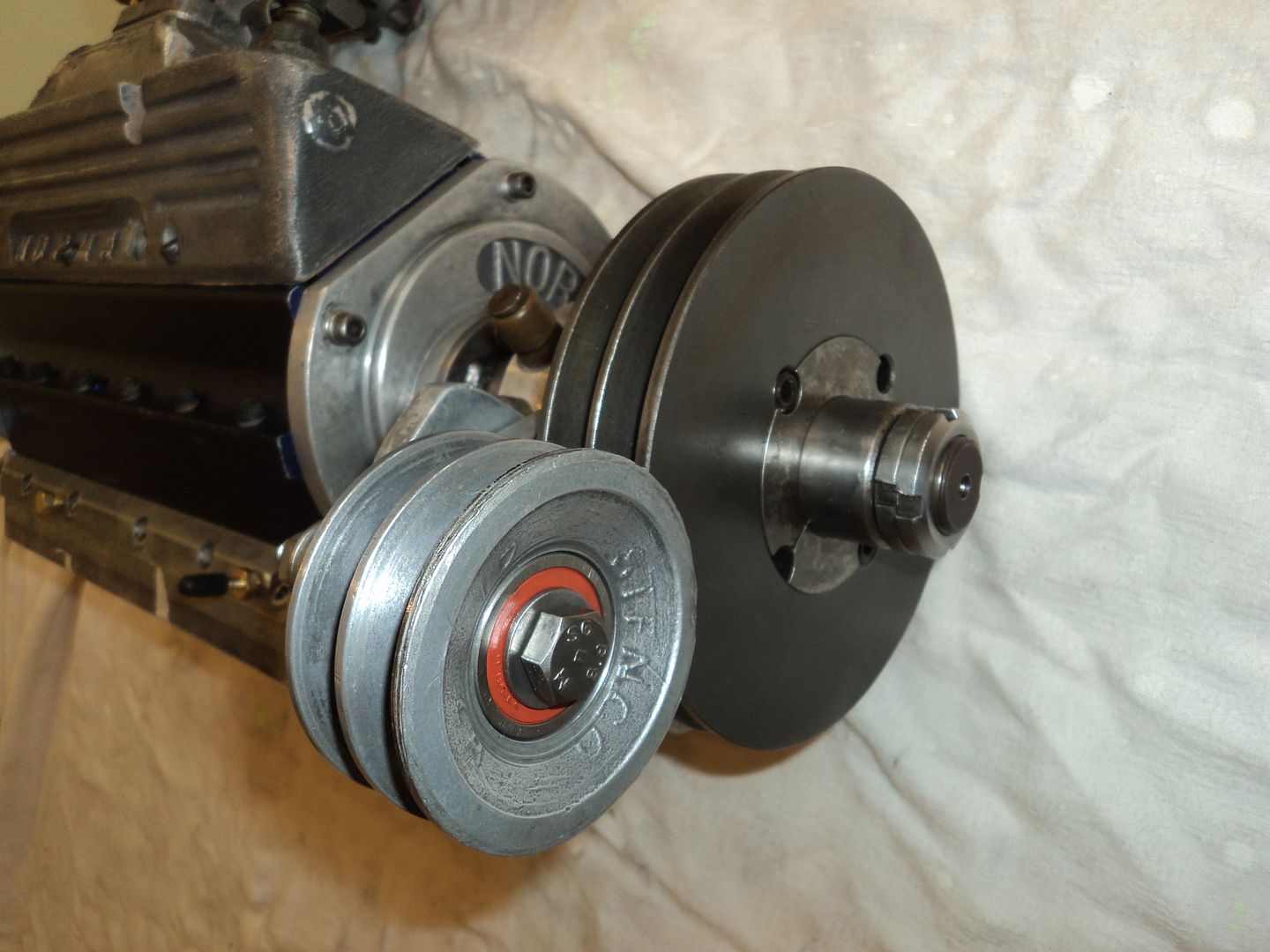

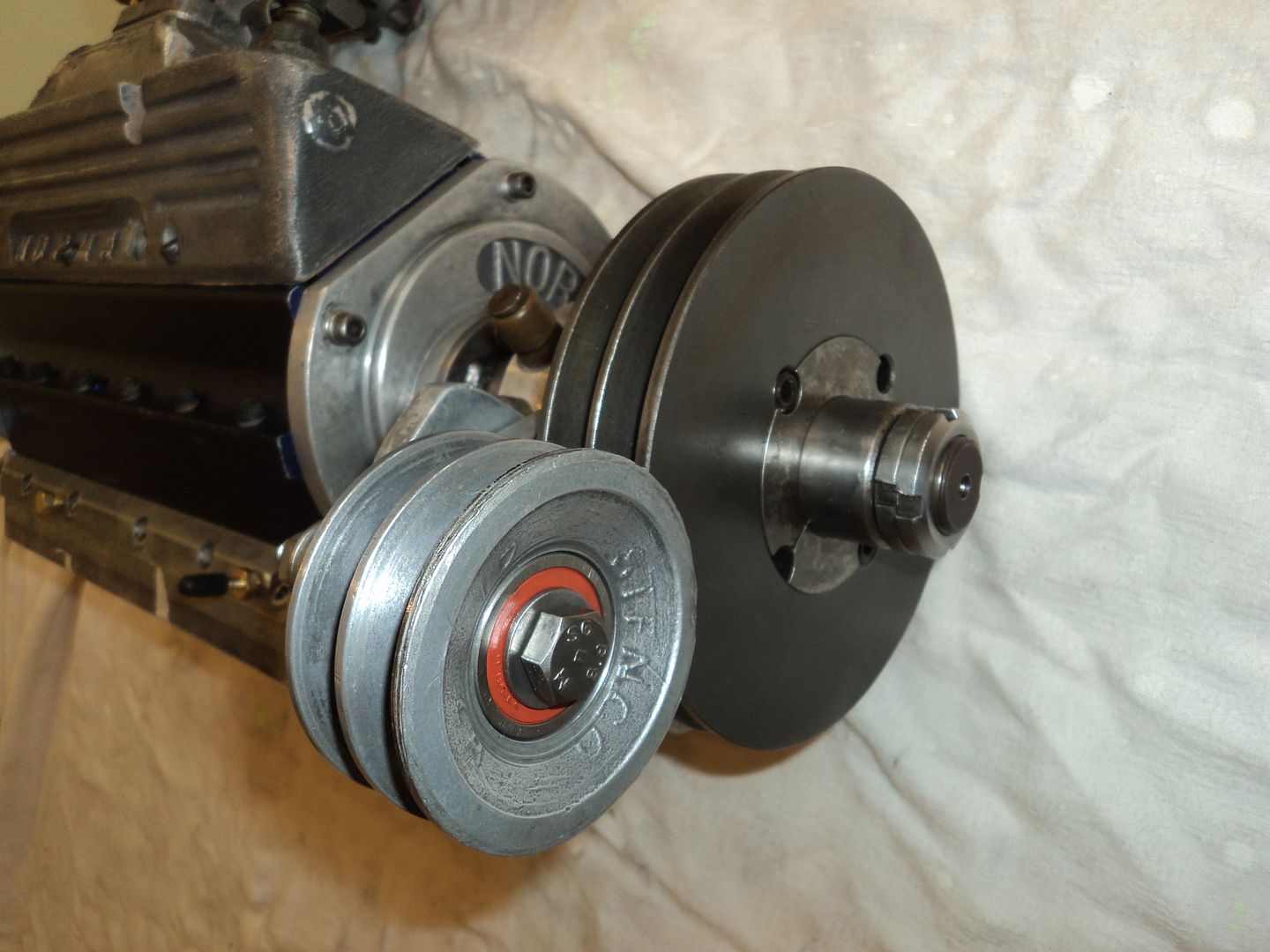

The shaft support assembly fits over the drive shaft between the end plate and the driven pulley, and is fastened onto the end plate by set screws. The intent of the shaft support is to provide a location for the belt tensioner to mount – the photo above shows the belt tensioner clamped in place over the tensioner. The drive shaft spins, but the shaft support remains static, with the belt tensioner clamped over it. In the image above, to the left of the red arrow

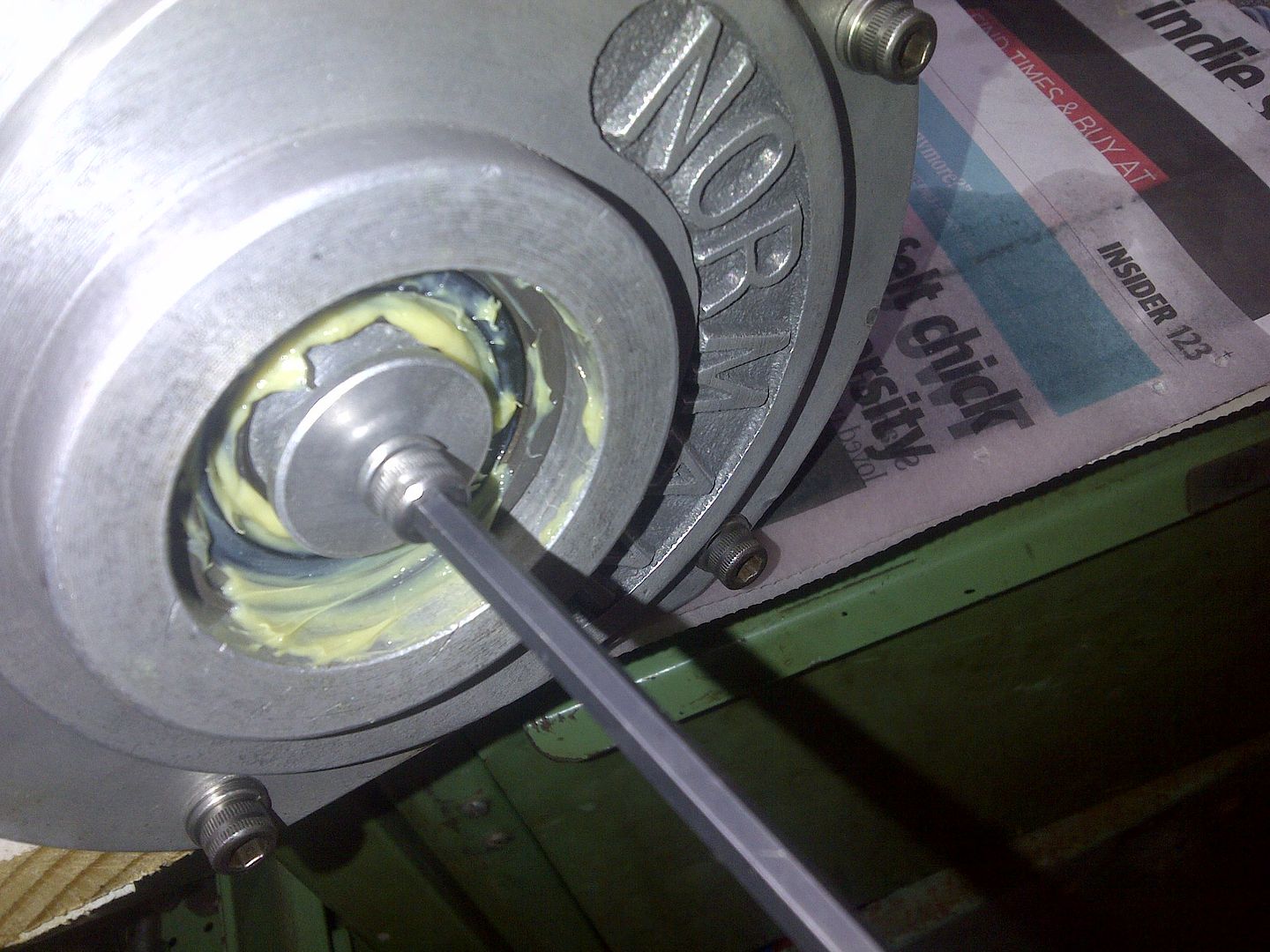

The image below shows Gary’s shaft support.

From left to right on the newspaper:

a) A mild-steel ring. One side pushes up against the supercharger drive-end bearing, the other is pushed on by the inboard shaft support assembly bearing.

b) The inboard shaft support assembly bearing. This allows the shaft to spin whilst the idler pulley arm remains static.

c) A long mild-steel spacer. One side pushes up against the inboard shaft support assembly bearing, the other side is pushed on by the outboard shaft support assembly bearing. Notice that above this spacer in the photo is the shaft support itself. It runs on the outside of the bearings, with the long mild-steel spacer running inside it.

d) The outboard shaft support assembly bearing.

e) A second mild-steel spacer. One side pushes up against the outboard shaft support assembly bearing, the other side pushes up against the drive pulley hub.

f) The greaser seal. This is designed to keep grease inside the shaft support.

g) The drive pulley hub. One side pushes up against the second mild-steel spacer, the other is held in place by the jam nuts. The drive pulley hub mounts the drive pulley.

h) The jam nuts. These push the whole assembly together and are installed on the end of the supercharger shaft thread. Note that these are castellated nuts, and need a hook-spanner to get them off.

The shaft support has a grease nipple fitted to it (in the little hole in the photo above, though absent from the photo). It also has a grease relief valve, fitted into an aluminium grease ring that slides over the shaft support. The grease ring is sealed to the shaft support by o-rings, and is fed grease from the shaft support through the big hole in the photo above. The basic lineup (without any shaft spacers) is shown below:

The intent is to pump grease into the annulus between the long mild-steel spacer and the shaft support – where my finger is sitting in the photo below.

The grease then runs left and right along the shaft, and into the inboard and outboard bearings – where those orange bits are in the photo above. Any excess grease pressure then vents out the grease relief valve. This prevents the grease gun from pressuring up the annulus, and bending the crap out of the bearing inner races (bear in mind that a grease gun can exert incredible hydraulic pressure… 15,000psi). Note that this only greases the shaft support bearings, not the supercharger bearings. Of note, the modern bearings I have fitted to Gary’s Norman are sealed. In the photos above, you can see orange rings on the bearings. These sealing rings keep grit and crap out, and the bearing grease (installed at the bearing factory) permanently in. This means that there is no need for regreasing, and that the shaft support grease nipple and relief valve are redundant.

Cheers,

Harv (deputy apprentice Norman supercharger fiddler).

As I was overhauling Gary’s 350 Norman, I took detailed notes and photos to send to him. I’ve finally had some time to trawl back through my notes and pull out some of the learnings. The post below covers them, albeit in no particular order.

When the original vanes were pulled from the Norman, it was apparent that they had started to suffer from delamination. The photo below shows two of the vanes, with the delaminations highlighted by the match heads.

For replacement vanes, I got hold of some F57 (a Bakelite replacement which we have discussed before). The photo below (from top to bottom) shows the original Norman vane, an F57 vane cut to size, the F57 vane blank and a Bakelite vane blank.

Note that I now have a stockpile of both F57 and Bakelite vane blanks. They are large enough that they will suit all Normans, with the exception of the Type 270, Type 265 and perhaps Type 90 (never had one of these three apart). If anyone wants some, give me a yell. I also have the replacement Inconel valve springs that prevent spring shattering.

I started by cutting them the F57 blank length (see diagram), going slightly oversized.

This is a short length of cut, and easy to do with a hacksaw. The length needs to be then lapped down so that the vanes are exactly as long as the rotor. I held off lapping until the vanes were trimmed for depth. The next cut I needed to make was for height. This is a looooong cut, and a hacksaw would give a very wobbly finish. This needs to be fairly straight, as it provides a flat scraping/sealing surface against the casing wall. To do this, I put the angle grinder into a drop-saw jig, and set up a fence to run the vane along. This gives a nice, parallel and neat cut.

The final "cut" I needed to make was for depth. This is done by lapping the vanes down on lapping plates, aiming for a flop fit in the rotor. I’ve made up the lapping tool to do so (see drawing) out of some angle iron.

The superchargers made by Mike Norman have steel liners pressed into the vane slots and riveted in place. Interestingly (…maybe frustratingly), the resultant vane liner slot is nowhere near parallel. The root of the slot is narrower, whilst the drive end overall depth is narrower than the non-drive end. This makes the lapping a fun process – as the vane is rubbed against the lapping plate, you need to bear down slightly harder on the areas that need to be less deep. I was lapping with 80 grit paper, and spent quite some time on just one vane – the Kevlar reinforcing is softer than the sandpaper, but still resistant to being abraded. In the end, I went back to P40 paper, then smoothed out with finer grades.

Having got the vanes sized correctly, I lapped down the length dimension - fit to rotor, check how much the vane hangs out, lap it down, repeat... a lot. With the dimensions finalised, I cut the spring notches and ground the relief grooves on the back of all three, using a diegrinder then flat file. The relief grooves are oriented on the downstream (low pressure) side of the vane. This configuration allows the vane slot root to vent. As the vanes operate in an oil film, there is a chance that the vanes form a seal in the vane slot, and either draw a vacuum at the vane root when sliding out, or build pressure at the vane root when sliding in. The grooves allow the vane root to vent, preventing the vane sealing with oil and not being able to rise/fall in the vane slot. An alternative way would have been to machine the relief grooves on the upstream (high pressure) side of the vane. The theory in that type of location is that higher pressure air/fuel can get under the vane and lift it, increasing vane seating pressure and getting a better seal. I have not seen this configuration put into place in Norman superchargers, but have heard of it being done for some Wray superchargers. The finished vanes are shown in the image below, along with the original Norman vanes.

Another lesson learnt on the 350 Norman relates to the end-plate gaskets. None of the Normans made by Mike Norman that I have pulled apart have had these gaskets (whilst Eldred’d did). The gaskets seal the end plates to the casing. They also provide a means of setting non-drive end clearance, by varying gasket thickness. In the case of Gary’s 250 Norman, the non-drive end clearance was sufficient that gasekts were not required to increase clearance. To seal the end plates to the casing, I used a thin bead of sealant in the groove that exists for exactly that purpose (even if we used gaskets, I would still add the sealant). This is very different to Eldred’s Normans, which have no groove and needs some form of gasket to seal. I used a fine bead of Permatex Ultra Black sealant in the sealing groove. This is a highly flexible oil resistant sealant, good for up to 260°C (intermittent) service.

In some of Mike’s Normans a long drive shaft was ordered by the customer. This allows the supercharger to be mounted further back along the engine and still line up with the crank pulley. The longer drive shafts were fitted with a support assembly, indicated by the arrow in the diagram below:

The shaft support assembly fits over the drive shaft between the end plate and the driven pulley, and is fastened onto the end plate by set screws. The intent of the shaft support is to provide a location for the belt tensioner to mount – the photo above shows the belt tensioner clamped in place over the tensioner. The drive shaft spins, but the shaft support remains static, with the belt tensioner clamped over it. In the image above, to the left of the red arrow

The image below shows Gary’s shaft support.

From left to right on the newspaper:

a) A mild-steel ring. One side pushes up against the supercharger drive-end bearing, the other is pushed on by the inboard shaft support assembly bearing.

b) The inboard shaft support assembly bearing. This allows the shaft to spin whilst the idler pulley arm remains static.

c) A long mild-steel spacer. One side pushes up against the inboard shaft support assembly bearing, the other side is pushed on by the outboard shaft support assembly bearing. Notice that above this spacer in the photo is the shaft support itself. It runs on the outside of the bearings, with the long mild-steel spacer running inside it.

d) The outboard shaft support assembly bearing.

e) A second mild-steel spacer. One side pushes up against the outboard shaft support assembly bearing, the other side pushes up against the drive pulley hub.

f) The greaser seal. This is designed to keep grease inside the shaft support.

g) The drive pulley hub. One side pushes up against the second mild-steel spacer, the other is held in place by the jam nuts. The drive pulley hub mounts the drive pulley.

h) The jam nuts. These push the whole assembly together and are installed on the end of the supercharger shaft thread. Note that these are castellated nuts, and need a hook-spanner to get them off.

The shaft support has a grease nipple fitted to it (in the little hole in the photo above, though absent from the photo). It also has a grease relief valve, fitted into an aluminium grease ring that slides over the shaft support. The grease ring is sealed to the shaft support by o-rings, and is fed grease from the shaft support through the big hole in the photo above. The basic lineup (without any shaft spacers) is shown below:

The intent is to pump grease into the annulus between the long mild-steel spacer and the shaft support – where my finger is sitting in the photo below.

The grease then runs left and right along the shaft, and into the inboard and outboard bearings – where those orange bits are in the photo above. Any excess grease pressure then vents out the grease relief valve. This prevents the grease gun from pressuring up the annulus, and bending the crap out of the bearing inner races (bear in mind that a grease gun can exert incredible hydraulic pressure… 15,000psi). Note that this only greases the shaft support bearings, not the supercharger bearings. Of note, the modern bearings I have fitted to Gary’s Norman are sealed. In the photos above, you can see orange rings on the bearings. These sealing rings keep grit and crap out, and the bearing grease (installed at the bearing factory) permanently in. This means that there is no need for regreasing, and that the shaft support grease nipple and relief valve are redundant.

Cheers,

Harv (deputy apprentice Norman supercharger fiddler).

327 Chev EK wagon, original EK ute for Number 1 Daughter, an FB sedan meth monster project and a BB/MD grey motored FED.

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

love your work Harv

I started with nothing and still have most of it left.

Foundation member #61 of FB/EK Holden club of W.A.

Foundation member #61 of FB/EK Holden club of W.A.

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

Ladies and gents,

Some more info from Gary’s overhaul.

Similarly to Eldred’s superchargers, Mike’s superchargers used a cast manifold between the carburettor and the supercharger. The photos below show one of Mike’s manifolds. The manifold will fit the 350 and 400 Normans (and probably the 300), it appears to be too long to fit the shorter Normans (150, 200 and 250)

Whilst the manifold below is a genuine Norman manifold, it has been butchered a bit:

a) by welding on an inlet flange to suit an 1¾” SU carburettor (2 1/8” centres, square pitch),

b) by welding on a great big bit of aluminium bar to act as a carburettor spring return (with four holes to allow you to adjust spring tension), and

c) By welding up the tappings in either end of the manifold.

Eldred’s manifolds bolt directly to the supercharger using studs. As I found out the hard way, the stud holes in Eldred’s superchargers are not precisely spaced. Mike’s Normans however do not bolt the manifolds directly to the supercharger. The extruded aluminium supercharger casings are made with channels either side of the inlet and discharge ports. The channels are used to locate steel strips, with tapped holes drilled into the strips. Studs, or short set screws, are used to mount the manifolds to the steel strips. The manifolds are this not positively bolted to the superchager – they rely on the clamping force of the steel strips against the channel to stop the manifold moving. The photo below shows the channels and a steel strip being fitted in place.

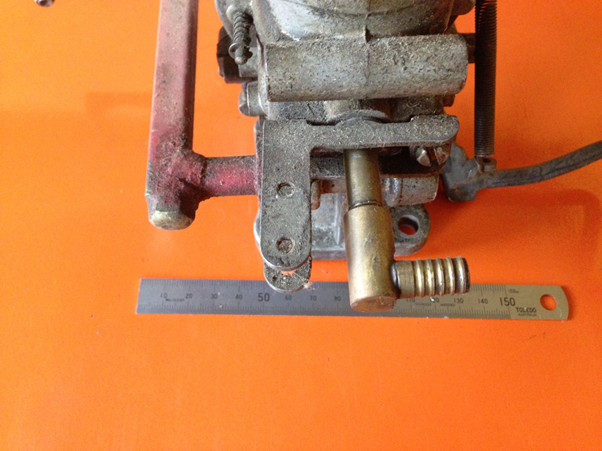

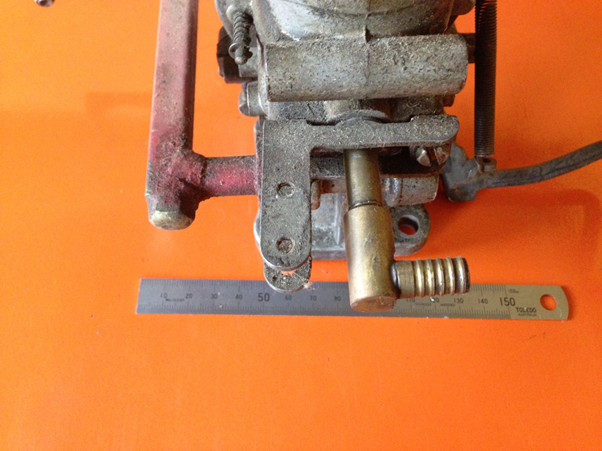

Pictured below is a home-made relief valve (from Gary’s 350 Norman), similar to the ones made by Weiand (part number 7155), The Blower Shop (part number 2589) and AussieSpeed (universal backfire valve).

This is a rubber-sealed rectangular plate held in place by two springs. Two studs screw into the aluminium adaptor, with some 5/16-14 UNC nyloc nuts used to compress the springs. The two brass sleeves shown in the photograph above are used to set how far the nuts can tighten – shorter sleeves let the nuts tighten more, which compresses the springs more, and gives a higher relief valve pressure. I really like the use of these brass spacers – they mean that every time the valve is reassembled, you know you are setting the correct relief valve pressure (provided the springs have not lost tension) and do not need to pop-test. The springs have a tension of 88lb/inch, and can compress from a free length of 1.169” down to 0.739” at coil bind (0.43” of compression). This means that between the two springs the clamping force is 0-76lb. The rectangular relief valve hole in the manifold has a cross section of some 0.92inch2. This means that the relief valve (with the current springs) can be set from 0-82psi. The current brass spacers give a spring compression of 0.338”, a clamping force of 59lb, and a set pressure of 64psi. Note that all the above is by calculation only, and would need to be verified by a pressure (pop) test before the manifold was used in anger. I’m not a big fan of nyloc nuts on relief valves, (which is why I used safety wire on Gary’s Type 65 relief valve), though it will work as long as the nyloc nuts are new. Not a good idea to reuse the nuts. Very, very rough calculations show that 4 inch2 of relief valve area is appropriate for the red motor type Normans (200ci/rev) operating around 4500rpm. The smaller Normans (80ci/rev) would still need around 2 inch2, though are safer at 4 inch2. This means that the relief valve shown above (0.92inch2) is a little small, as are the Weiand (0.8inch2) and The Blower Shop (0.44inch2) offerings. Relief valves of this size should either be doubled up (one at either end of the manifold) or used in conjunction with a burst plate.

One other item of note from Gary’s 350 Norman overhaul is that the rotor has a keeper fitted at the non-drive end of the rotor driveshaft. This consists of a set screw and washer, which fit into the tapped end of the rotor shaft.

The purpose of the retainer depends heavily on what size washer is used. One option is where the washer is sized such that it is small enough to pass through the bearing outer race. This allows the rotor to move as much as it wants relative to the casing, and only holds the bearing inner race onto the shaft (bear in mind that Norman non-drive end bearings are two piece, allowing the inner and outer races to slip over one another). Realistically, the bearing inner race is a press fit onto the shaft, and unlikely to move (i.e. this option is not very useful)

The better option is where the washer diameter is large enough to bear against the bearing outer race. With the rotor cold, the washer almost touches the bearing inner race. As the supercharger heats up, the rotor grows and the inner race moves towards the end of the casing. The distance between the washer and outer bearing increases. As the rotor cools again (when the vehicle is stopper), the washer approaches the outer race. If the rotor is given a shunt towards the drive end, the washer bears against the outer race, preventing the rotor rubbing on the drive-end end plate.

A further set of three keepers are fitted to the drive-end end plate. These small tabs retain the drive-end seal into the end plate, as per the image below. This prevents high boost pressure from driving out the seal. The drive end keepers appear to have been fitted to all of Mike’s Norman supercharger.

I have also seen similar keepers fitted to some Norman non-drive end end plates in order to prevent the welsh plug being blown out under boost.

Cheers,

Harv (deputy apprentice Norman supercharger fiddler).

Some more info from Gary’s overhaul.

Similarly to Eldred’s superchargers, Mike’s superchargers used a cast manifold between the carburettor and the supercharger. The photos below show one of Mike’s manifolds. The manifold will fit the 350 and 400 Normans (and probably the 300), it appears to be too long to fit the shorter Normans (150, 200 and 250)

Whilst the manifold below is a genuine Norman manifold, it has been butchered a bit:

a) by welding on an inlet flange to suit an 1¾” SU carburettor (2 1/8” centres, square pitch),

b) by welding on a great big bit of aluminium bar to act as a carburettor spring return (with four holes to allow you to adjust spring tension), and

c) By welding up the tappings in either end of the manifold.

Eldred’s manifolds bolt directly to the supercharger using studs. As I found out the hard way, the stud holes in Eldred’s superchargers are not precisely spaced. Mike’s Normans however do not bolt the manifolds directly to the supercharger. The extruded aluminium supercharger casings are made with channels either side of the inlet and discharge ports. The channels are used to locate steel strips, with tapped holes drilled into the strips. Studs, or short set screws, are used to mount the manifolds to the steel strips. The manifolds are this not positively bolted to the superchager – they rely on the clamping force of the steel strips against the channel to stop the manifold moving. The photo below shows the channels and a steel strip being fitted in place.

Pictured below is a home-made relief valve (from Gary’s 350 Norman), similar to the ones made by Weiand (part number 7155), The Blower Shop (part number 2589) and AussieSpeed (universal backfire valve).

This is a rubber-sealed rectangular plate held in place by two springs. Two studs screw into the aluminium adaptor, with some 5/16-14 UNC nyloc nuts used to compress the springs. The two brass sleeves shown in the photograph above are used to set how far the nuts can tighten – shorter sleeves let the nuts tighten more, which compresses the springs more, and gives a higher relief valve pressure. I really like the use of these brass spacers – they mean that every time the valve is reassembled, you know you are setting the correct relief valve pressure (provided the springs have not lost tension) and do not need to pop-test. The springs have a tension of 88lb/inch, and can compress from a free length of 1.169” down to 0.739” at coil bind (0.43” of compression). This means that between the two springs the clamping force is 0-76lb. The rectangular relief valve hole in the manifold has a cross section of some 0.92inch2. This means that the relief valve (with the current springs) can be set from 0-82psi. The current brass spacers give a spring compression of 0.338”, a clamping force of 59lb, and a set pressure of 64psi. Note that all the above is by calculation only, and would need to be verified by a pressure (pop) test before the manifold was used in anger. I’m not a big fan of nyloc nuts on relief valves, (which is why I used safety wire on Gary’s Type 65 relief valve), though it will work as long as the nyloc nuts are new. Not a good idea to reuse the nuts. Very, very rough calculations show that 4 inch2 of relief valve area is appropriate for the red motor type Normans (200ci/rev) operating around 4500rpm. The smaller Normans (80ci/rev) would still need around 2 inch2, though are safer at 4 inch2. This means that the relief valve shown above (0.92inch2) is a little small, as are the Weiand (0.8inch2) and The Blower Shop (0.44inch2) offerings. Relief valves of this size should either be doubled up (one at either end of the manifold) or used in conjunction with a burst plate.

One other item of note from Gary’s 350 Norman overhaul is that the rotor has a keeper fitted at the non-drive end of the rotor driveshaft. This consists of a set screw and washer, which fit into the tapped end of the rotor shaft.

The purpose of the retainer depends heavily on what size washer is used. One option is where the washer is sized such that it is small enough to pass through the bearing outer race. This allows the rotor to move as much as it wants relative to the casing, and only holds the bearing inner race onto the shaft (bear in mind that Norman non-drive end bearings are two piece, allowing the inner and outer races to slip over one another). Realistically, the bearing inner race is a press fit onto the shaft, and unlikely to move (i.e. this option is not very useful)

The better option is where the washer diameter is large enough to bear against the bearing outer race. With the rotor cold, the washer almost touches the bearing inner race. As the supercharger heats up, the rotor grows and the inner race moves towards the end of the casing. The distance between the washer and outer bearing increases. As the rotor cools again (when the vehicle is stopper), the washer approaches the outer race. If the rotor is given a shunt towards the drive end, the washer bears against the outer race, preventing the rotor rubbing on the drive-end end plate.

A further set of three keepers are fitted to the drive-end end plate. These small tabs retain the drive-end seal into the end plate, as per the image below. This prevents high boost pressure from driving out the seal. The drive end keepers appear to have been fitted to all of Mike’s Norman supercharger.

I have also seen similar keepers fitted to some Norman non-drive end end plates in order to prevent the welsh plug being blown out under boost.

Cheers,

Harv (deputy apprentice Norman supercharger fiddler).

327 Chev EK wagon, original EK ute for Number 1 Daughter, an FB sedan meth monster project and a BB/MD grey motored FED.

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

Great work Harv - they look like really well engineered units - wish they were more available - would love to fit the small unit with a mild cam and a good set of extractors to my grey - more for the beauty than the HP - add a cross flow head and it becomes a really nice little motor.

You will find me lost somewhere!

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

A nice expensive little motor tooFJWALLY wrote:Great work Harv - they look like really well engineered units - wish they were more available - would love to fit the small unit with a mild cam and a good set of extractors to my grey - more for the beauty than the HP - add a cross flow head and it becomes a really nice little motor.

I started with nothing and still have most of it left.

Foundation member #61 of FB/EK Holden club of W.A.

Foundation member #61 of FB/EK Holden club of W.A.

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

Sadly, I reckon so.Blacky wrote:A nice expensive little motor tooFJWALLY wrote:Great work Harv - they look like really well engineered units - wish they were more available - would love to fit the small unit with a mild cam and a good set of extractors to my grey - more for the beauty than the HP - add a cross flow head and it becomes a really nice little motor.

The supercharger purchase, rebuild and setup would set you back $3500 if you DIY, and ~$8000 if you could find someone who would sell you a running one.

The HighPower head will be in the $20,000 mark.

Figure another $3,000 for a decent rebuild of the grey.

All up $30,000-$40,000 for a 180BHP grey. It would be cool, but expensive for what it would be.

Cheers,

Harv

327 Chev EK wagon, original EK ute for Number 1 Daughter, an FB sedan meth monster project and a BB/MD grey motored FED.

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

Wow - ah well- we can always dream.

You will find me lost somewhere!

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

Ladies and gents,

As I’ve been working through the Norman supercharger history, I keep running across links to Australian motorsport. I’ve run across another such link, and am interested in hunting it down. It involves an air cooled Type 65 Norman that changed hands a few years ago. The Norman was running triple 1.25” SUs when sold. Heres some of the story:

Kevin Wood owned an Elfin 600 with a 1st series Toyota Celica engine and Norman supercharger. The blue vehicle was purchased for $2,000. Kevin did not run the Elfin with a body, instead using large wings front and rear. The Norman had been sourced from Barry Bray's Datsun 2000 powered A30 sports sedan, whilst the Elfin had once belonged to Barry Kirk. Kevin sold the Elfin to Roger Seward for $8500, who fitted a Lotus twin-cam and got a historic log book before onselling the Elfin for some $30,000. Peter Smeets bought the motor and Norman supercharger, and gave the Celica motor to Jim Doig for a bottle of red wine. The supercharger was sold to a person who was putting it on a FB Holden, along with a copy of Eldred’s Supercharge! book. This is the person I am hunting down. The FB owner was a young gentleman who worked at Bunnings Marion, South Australia.

Interested to hear from anyone who knows of the mysterious Marion owner.

Cheers,

Harv

As I’ve been working through the Norman supercharger history, I keep running across links to Australian motorsport. I’ve run across another such link, and am interested in hunting it down. It involves an air cooled Type 65 Norman that changed hands a few years ago. The Norman was running triple 1.25” SUs when sold. Heres some of the story:

Kevin Wood owned an Elfin 600 with a 1st series Toyota Celica engine and Norman supercharger. The blue vehicle was purchased for $2,000. Kevin did not run the Elfin with a body, instead using large wings front and rear. The Norman had been sourced from Barry Bray's Datsun 2000 powered A30 sports sedan, whilst the Elfin had once belonged to Barry Kirk. Kevin sold the Elfin to Roger Seward for $8500, who fitted a Lotus twin-cam and got a historic log book before onselling the Elfin for some $30,000. Peter Smeets bought the motor and Norman supercharger, and gave the Celica motor to Jim Doig for a bottle of red wine. The supercharger was sold to a person who was putting it on a FB Holden, along with a copy of Eldred’s Supercharge! book. This is the person I am hunting down. The FB owner was a young gentleman who worked at Bunnings Marion, South Australia.

Interested to hear from anyone who knows of the mysterious Marion owner.

Cheers,

Harv

327 Chev EK wagon, original EK ute for Number 1 Daughter, an FB sedan meth monster project and a BB/MD grey motored FED.

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

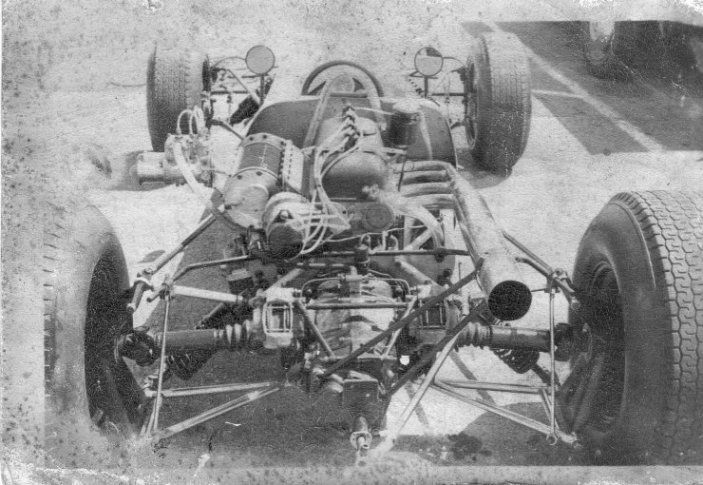

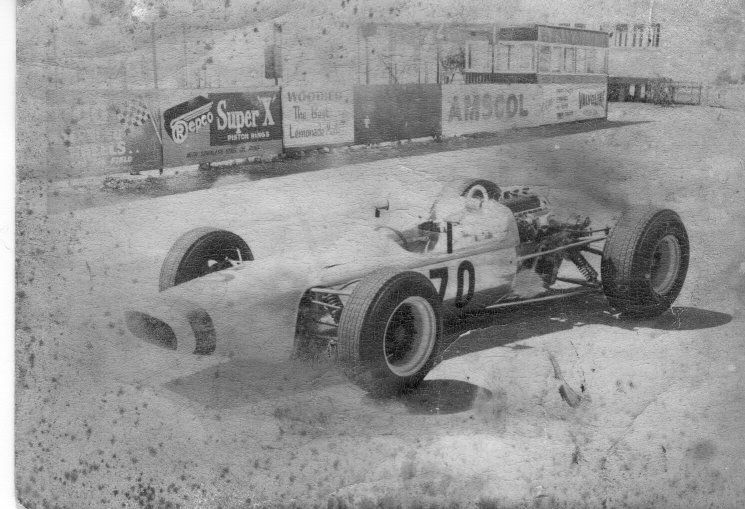

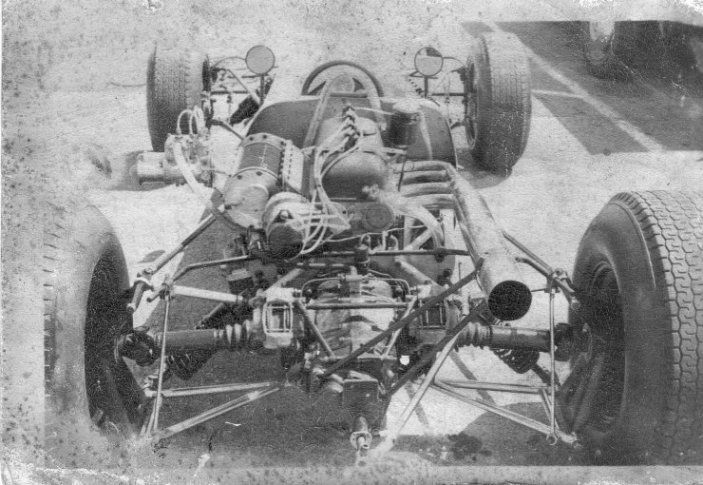

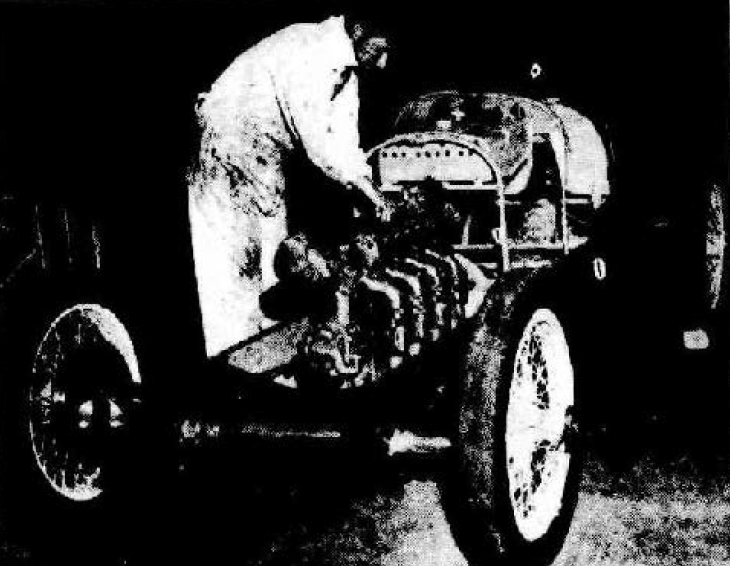

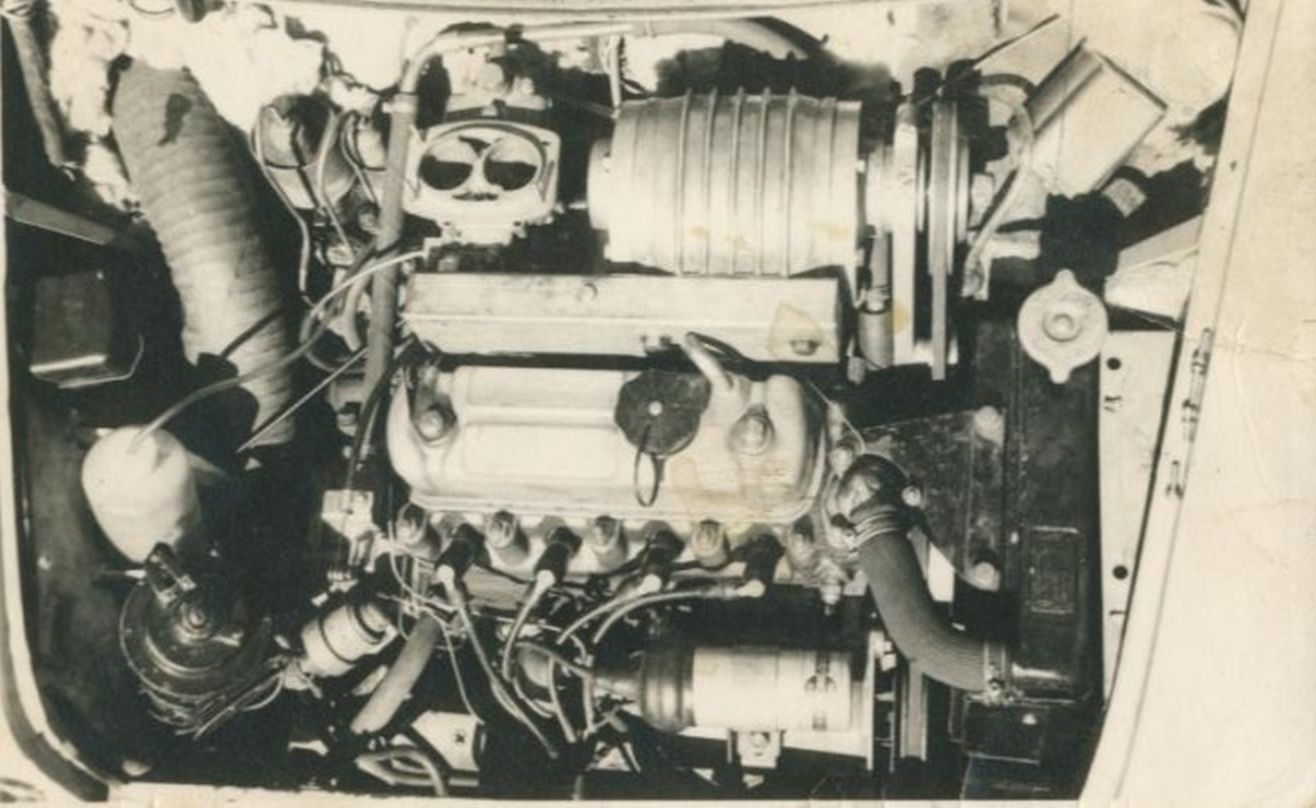

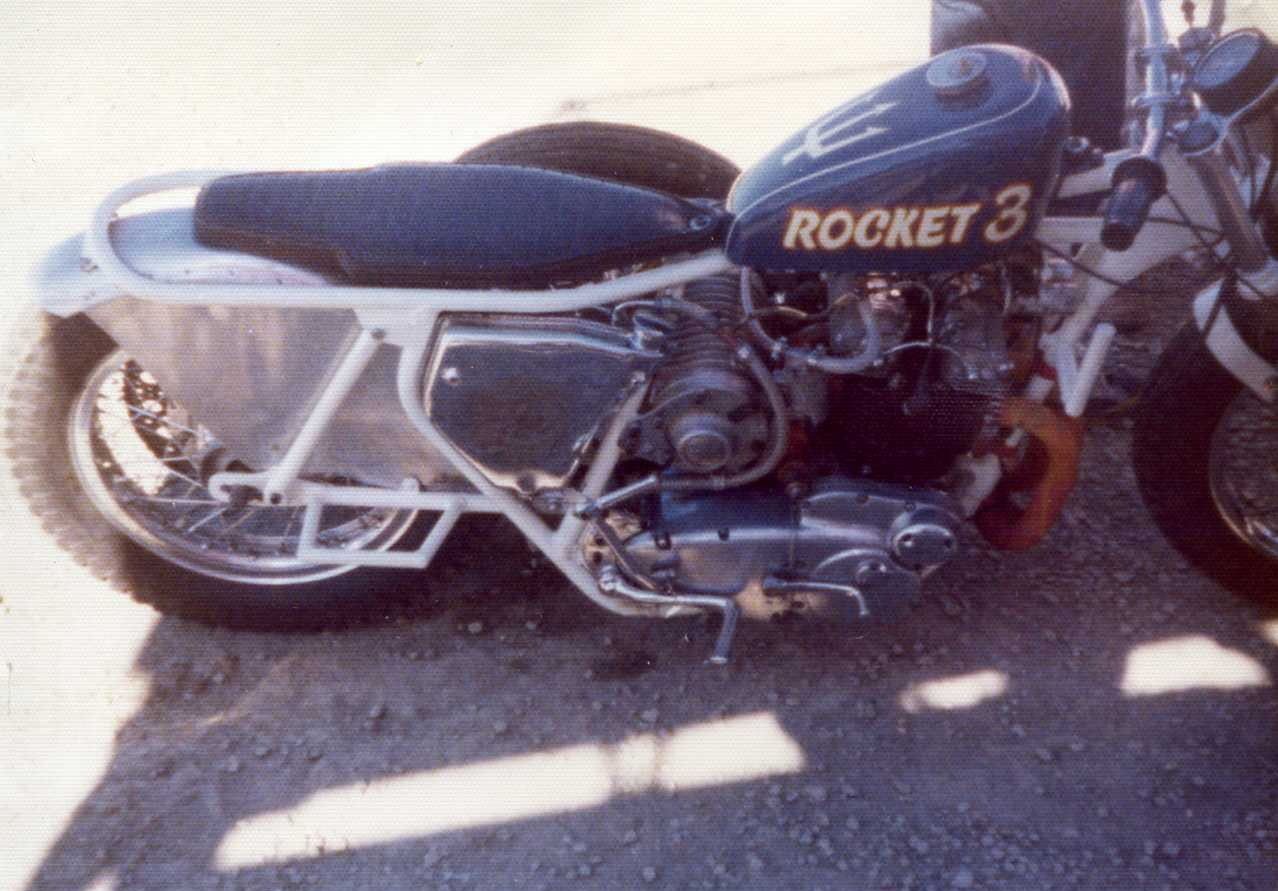

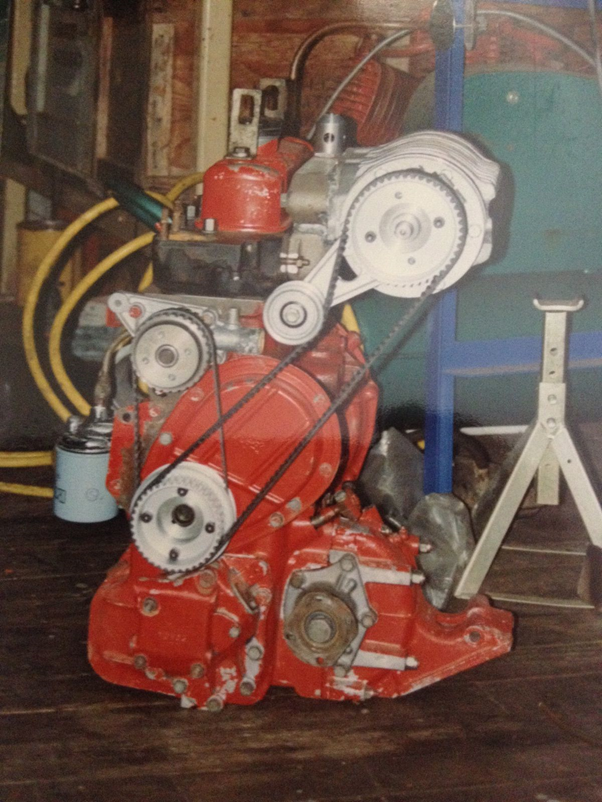

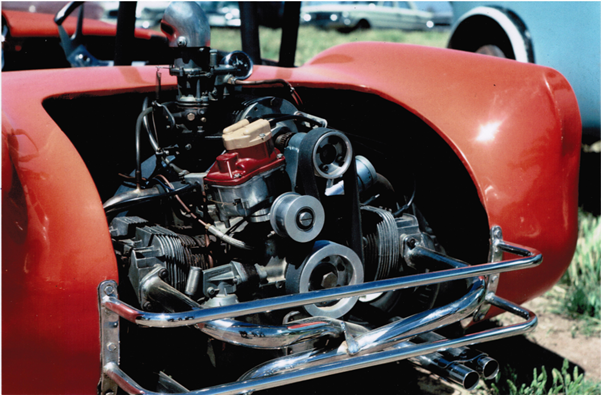

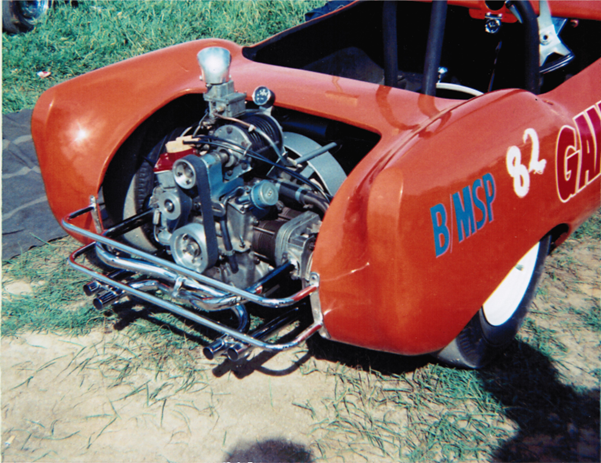

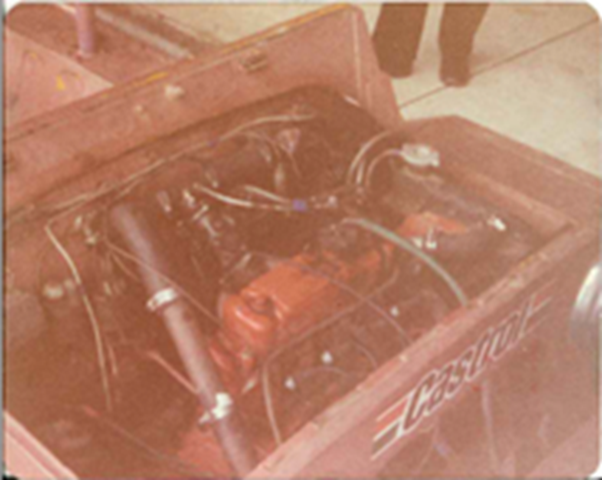

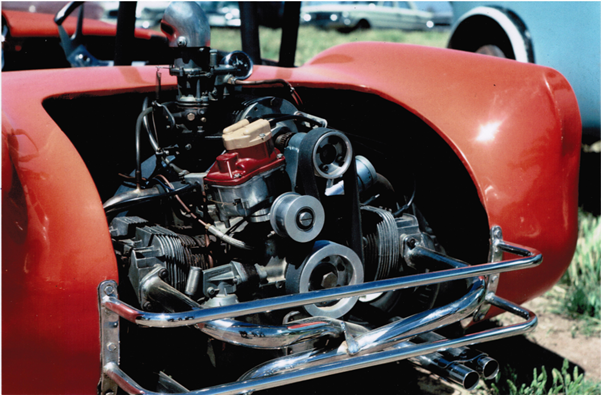

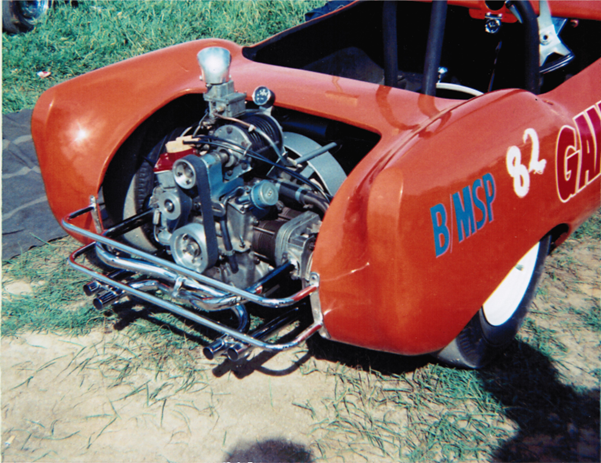

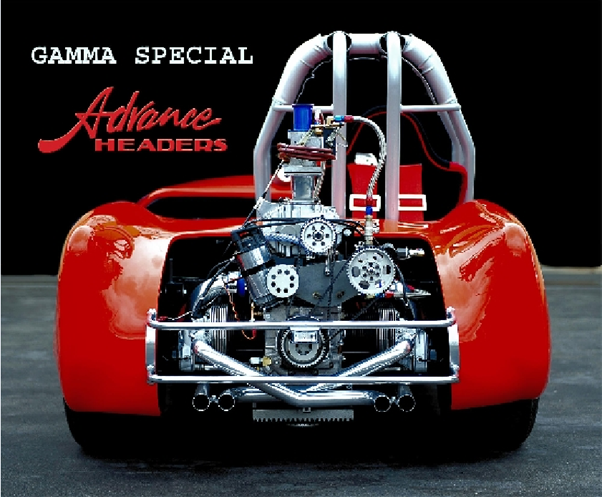

The photos below show Ian Richards self-built Viper Peugeot. The vehicle was built around 1967/1968.

Ian used to transport the Viper to various racing circuits on the tray of a Peugeot 403 utility, with parts of the Viper protruding into the utility cabin through a custom-made hole. Ian currently runs his own team of F3 cars, with a more refined transporter . In between times Ian built and raced the Richards F2 cars winning the 1983 Australian F2 title. Ian was an apprentice fitter and turner at Southcott’s when he built the car in his Mum’s shed. A fellow pattern making apprentice made the patterns for the rear uprights from a photo in a book complete with “Viper” cast into them. A chassis jig from the WRE (Weapons Research Establishment) car club was used to position the frame, which was then arc welded by a guy that worked at Holden’s using “very skinny electrodes” (race car chassis in this era were typically brazed together using nickel bronze). Ian cut the close ratio gears for the Volkswagen split case gear box himself, using ratios suggested by Garry Cooper (of Elfin fame). More assistance from Elfin came in the form of the nose cone, which was made by an Elfin panelman as an afterhours job at Ian’s mum’s shed. The car raced without wings initially, then with suspension mounted wings (which were banned worldwide after failures in F1 in Europe) then with chassis mounted wings.

. In between times Ian built and raced the Richards F2 cars winning the 1983 Australian F2 title. Ian was an apprentice fitter and turner at Southcott’s when he built the car in his Mum’s shed. A fellow pattern making apprentice made the patterns for the rear uprights from a photo in a book complete with “Viper” cast into them. A chassis jig from the WRE (Weapons Research Establishment) car club was used to position the frame, which was then arc welded by a guy that worked at Holden’s using “very skinny electrodes” (race car chassis in this era were typically brazed together using nickel bronze). Ian cut the close ratio gears for the Volkswagen split case gear box himself, using ratios suggested by Garry Cooper (of Elfin fame). More assistance from Elfin came in the form of the nose cone, which was made by an Elfin panelman as an afterhours job at Ian’s mum’s shed. The car raced without wings initially, then with suspension mounted wings (which were banned worldwide after failures in F1 in Europe) then with chassis mounted wings.

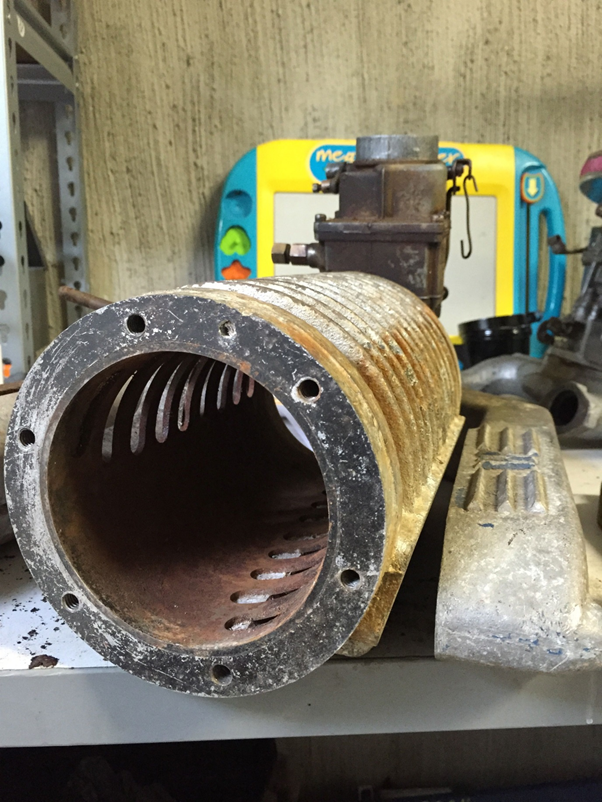

The Viper ran a Peugot 403 motor. However, the 403 motor tended to crack the block at the cylinder liners. The block was replaced with a 203 block, which was bored out to suit. Ian worked with Alec Rowe, with Alec being no stranger to Norman supercharged Peugeot motors. The Pug motor was fitted with an air-cooled iron cased Norman (very likely to have been a Type 65). The casing was lightened by machining some of the fins back. The heavy steel rotor was replaced with a lightweight aluminum unit, with steel driveshafts pressed in. Boost was around 8-10psi. The Norman had a tendency to break the lightweight rotors, with replacement units having the vane root web thickness increased. The Viper ran a single DCOE Weber carburettor on alcohol, with a supplementary fuel injection to provide enrichment as not enough methanol would flow through the Weber.

I believe the photos below show the car in later revisions, with some changes in induction evident. The Norman however remained on the vehicle throughout it’s life. The vehicle was eventually broken up, with the Norman-blown pug motor being fitted by Ian into a speedcar owned by Dennis Freeman. The back-end of the vehicle would find a home in a Corolla Sports Sedan in Port Pirie.

Cheers,

Harv

Ian used to transport the Viper to various racing circuits on the tray of a Peugeot 403 utility, with parts of the Viper protruding into the utility cabin through a custom-made hole. Ian currently runs his own team of F3 cars, with a more refined transporter

The Viper ran a Peugot 403 motor. However, the 403 motor tended to crack the block at the cylinder liners. The block was replaced with a 203 block, which was bored out to suit. Ian worked with Alec Rowe, with Alec being no stranger to Norman supercharged Peugeot motors. The Pug motor was fitted with an air-cooled iron cased Norman (very likely to have been a Type 65). The casing was lightened by machining some of the fins back. The heavy steel rotor was replaced with a lightweight aluminum unit, with steel driveshafts pressed in. Boost was around 8-10psi. The Norman had a tendency to break the lightweight rotors, with replacement units having the vane root web thickness increased. The Viper ran a single DCOE Weber carburettor on alcohol, with a supplementary fuel injection to provide enrichment as not enough methanol would flow through the Weber.

I believe the photos below show the car in later revisions, with some changes in induction evident. The Norman however remained on the vehicle throughout it’s life. The vehicle was eventually broken up, with the Norman-blown pug motor being fitted by Ian into a speedcar owned by Dennis Freeman. The back-end of the vehicle would find a home in a Corolla Sports Sedan in Port Pirie.

Cheers,

Harv

327 Chev EK wagon, original EK ute for Number 1 Daughter, an FB sedan meth monster project and a BB/MD grey motored FED.

Re: Harv's Norman supercharger thread

Ladies and gentlemen,

Following on from my Eldred Norman anecdote, I got to thinking about the period in Australia’s automotive history. The 1950’s and 1960’s were a period where we still relied heavily on local product – the market flooding of readily available imported go-fast parts for the small block Chev had yet to occur. This need for local equipment spurred on some very cool Australian engineering, including Eldred’s work. In the local forced induction field, there were numerous people bolting on (or making kits for) imported superchargers. This is a phenomena we see today with both Harrop (who kit out the Eaton TVS machines), the Castlemaine Rod Shop (who kit out the Aisin SC14 machine), and Yella Terra (who kit out the Eaton M90). Sprintex are perhaps the only Australian company who manufacture their own (twin screw) machines.

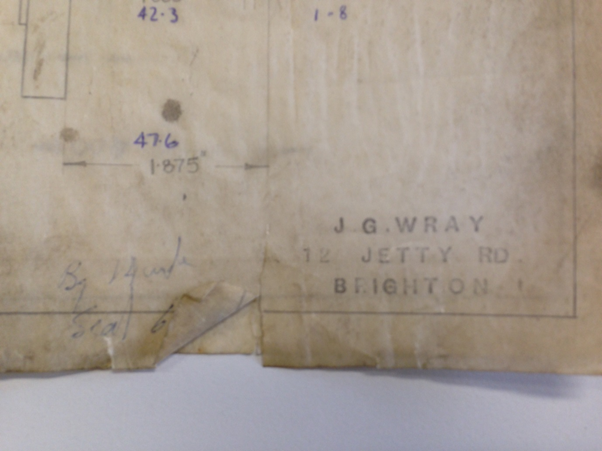

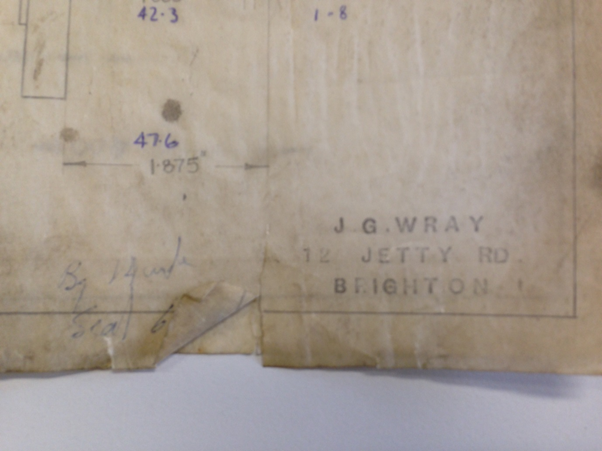

What is interesting (and also rather cool) is that Eldred was not the only Australian who was manufacturing superchargers (and not just kits) in the 1950’s and 1960’s period. One of Eldred’s contemporaries, competitors, and fellow South Australian was John G. Wray. The anecdote below tries to paint a picture of the Wray supercharger history. Just like my Eldred Norman anecdote, a word of warning regarding the information below. Some of the people who witnessed the events below have sadly passed away, including John Wray. It has also been half a century since the Wray supercharger was conceived. This anecdote has been written drawing together information from a broad variety of sources, many of whom are trying to remember events of fifty years ago. There may be inconsistencies with the information, or outright errors. Caveat emptor. I also owe a debt of thanks to a great number of people who helped pulled together the pieces of the “patchwork quilt” that became my Wray anecdote.

1. J.G. Wray

John Graham Wray was born in 1930, at an unknown location, in Australia. John married, and he and his wife Margaret did not have children. John spent some of his early years in England with his wife on a working holiday. His interest there was in automotive engineering and sporting cars. On return to Australia John was working as a Castrol sales representative, with Margaret working as a nurse. Over time John accumulated quite a few engineering tools and machines. He eventually started a small engineering shop (J.G. Wray General & Maintenance Engineering) at Newman Lane Glenelg, South Australia. The shop catered for general and maintenance engineering with John and staff being involved with the following activities:

• Small production runs of components for machinery,

• Design, manufacture and maintenance of machinery for the testing and manufacturing of automotive components,

• Design, manufacture and maintenance of machinery for the textile industry,

• Manufacture of marine components,

• Manufacture and maintenance of mining equipment, and

• Jobbing and ‘one off’ work.

Wray Engineering raised patents for example on a “burr beater” agricultural implement.

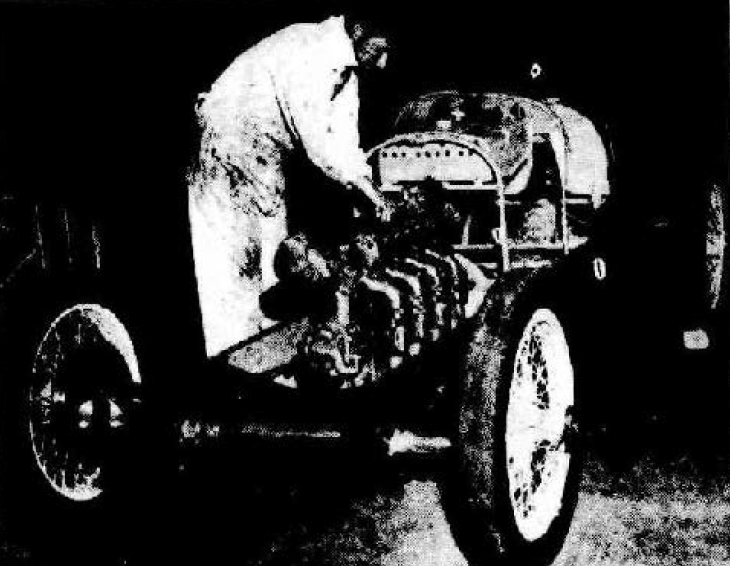

John owned a white hardtop MGA 1558cc twin-cam that he either brought back from or imported from the UK. He later sold the MGA to purchase an Alpha Romeo GTA. John’s main interest at that time was with yachts, bringing with that interest numerous customers to the company with the manufacture and development of marine parts and marine maintenance. John constructed a 30ft double-ended fibreglass ocean going yacht in one of the workshop bays. He used the yacht for many years until health issues forced him to sell it. His other interest in later years was exploring outback Australia in his 4WD. John passed away about eight years ago in Adelaide. The following article is drawn from the (Adelaide) Advertiser of the 14th of October 1954:

Vintage Racing Car Has History

Historic Racer

A vintage racing car, now being rebuilt in South Australia, has one of the most colourful histories of any vehicle in this State, and because of its age an even more colourful one than the ex-Prince Birabongse, MG K3, owned by Andy Brown. The car is a 1923 2-litre Miller, owned by Gordon Haviland, and at present being rebuilt by John Wray and Len Poultridge. Believed to be the first Miller to leave America, the car was taken to Europe in 1923 with two other Millers to compete in under 2-litre formula races. Count Louis Zborowski took delivery of the first car and entered it in the Spanish Grand Prix, run at Sitges-Terramar, in which he finished second. The other Millers also ran against Zborowski in the Grand Prix de l’Europe, at Monza, one of them, driven by Murphy, scoring third position. Count Zborowski kept his car when the other two returned to the US, and raced it in late 1923 and early 1924 before competing in the 1924 French Grand Prix. Well known author and writer in 'Autocar,' S. C. H. Davis was Zborowski's mechanic on this occasion. The introduction of the supercharger on other vehicles gave the Miller a considerable disadvantage in this event, but when 'blowers' were fitted, an American driver, Harry Hartz, covered 50 miles at 135 m.p.h in 1925. The Miller did not finish in the French Grand Prix, and Count Zborowski was killed at Monza shortly afterwards when his Mercedes skidded into a tree during the running of the Italian Grand Prix. All Zborowski's cars were then sold. The car was bought by Dan Higgen and raced at Southport Sands, in England in 1925. The Miller covered the flying kilometre in 25 seconds, and finished fourth. It raced in several events at Brooklands and in other meetings during 1925 and 1926. The car came to Australia a year or so later. It has had several owners in this country and competed in numerous hill climb and other events. The body has been lowered, but it still retains its original Miller engine. Picture shows John Wray working on the car this week.

A South Australian with a passion for old race vehicles who goes on to build his own superchargers? Sounds like another gentleman we have met before . As an aside, Count Zborowski built and raced the original Chitty Chitty Bang Bang… with a 23-litre Maybach aero engine (!). The Miller 122 shown in the photograph above is centrifugally supercharged.

Wray superchargers were manufactured at the Glenelg factory up until about 1967. The company moved to larger premises at nearby 46 Byre Avenue, Somerton Park in 1970 (now home to Tintworks window tinting), where production continued until about 1983. The image below, lifted from the internet, shows the Somerton Park facility in 2009, which is very similar to how it looked in the early 1980s.

John Wray’s direct involvement in the manufacture of the superchargers continued until about 1974. Wray superchargers manufactured after that time were still made at Wray Engineering, but manufactured by staff after hours and on weekends, with little to no advice from John. Batches of superchargers would be made, and sold to speed shops. It is estimated that around fifty superchargers were built in this fashion. Whilst quite a few people were employed at the Wray works, a few were heavily involved in the supercharger side of the business. James (Robbie) Robinson started at the Glenelg workshop and moved to Somerton Park. He was a leading hand until he left about the mid 1970’s. Greg Pill started as an apprentice in 1970 and worked there until 1985, having been a leading hand for about nine years. Robert (Bob) Cronin worked as a machinist from about 1975 until 1983. We will hear more about Robbie, Greg and Bob (and their vehicles) later in this anecdote.

2. Wray Supercharger Models

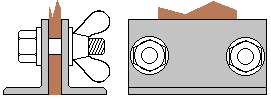

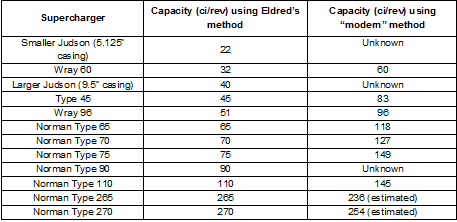

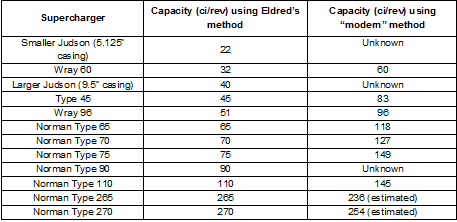

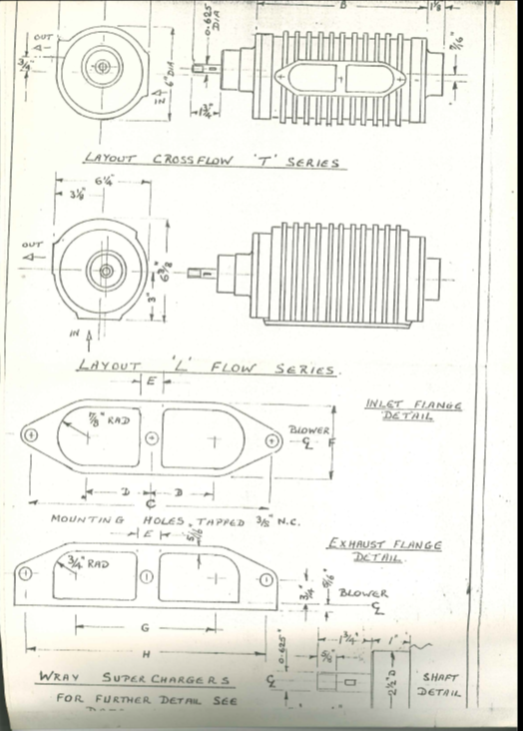

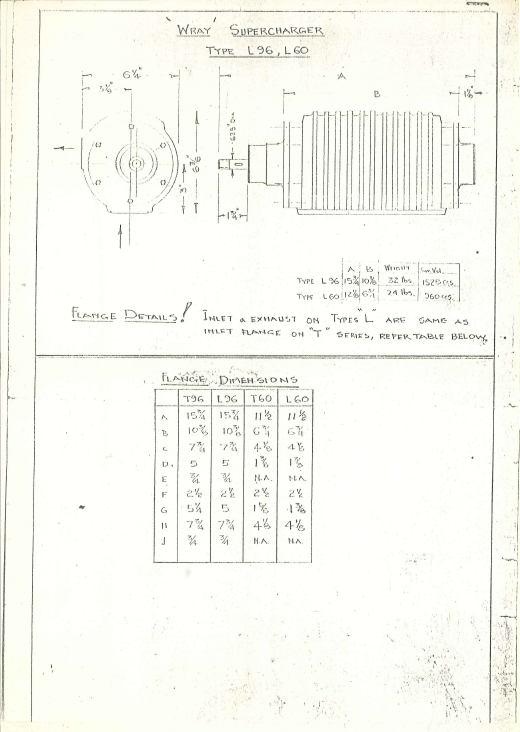

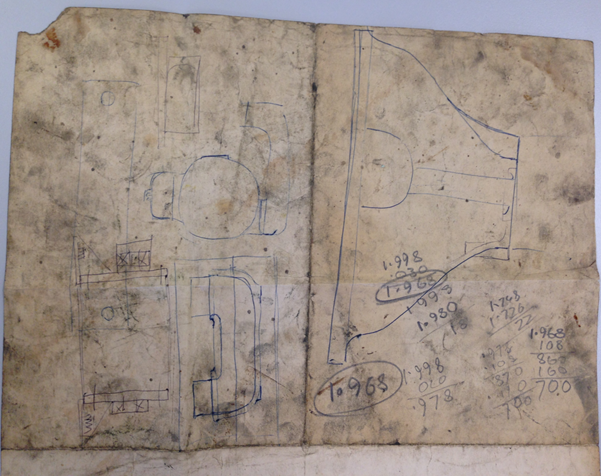

Like the Norman and Judson superchargers, the Wray supercharger was a sliding vane unit operating at relatively low pressure (~5psi boost). Like the Judson, and unlike some Normans, all Wray supercharger casings are 100% air-cooled. Wray offered two sizes, the smaller having a displacement of 60ci/rev (960cc) and the larger a displacement of 96ci/rev (1530cc). Note that these capacities of swept volume are calculated using the “modern” method of measuring them. In the example drawing below this means work out the volume shown in red, and multiplying it by six (yes, yes, I know, the Wray has four vanes… . it’s just an example ).

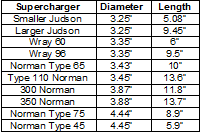

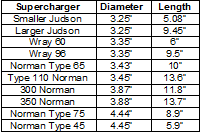

An alternate method was used in this period by Eldred Norman (and is noted in his book Supercharge!). Referring to the drawing above, Eldred’s method determines the volume shown in orange. Eldred’s method is neither more right nor more wrong than the “modern” method… just different. It also gives different results – a lot smaller number than the modern method. As an example, when we measure a Type 65 Norman supercharger using the modern method, we get 118ci/rev. However, when we measure the Type 65 using Eldred’s method, we get 67ci/rev (near enough to 65ci, and hence the name). The modern method is heavily dependent on port timing, whereas Eldred’s method is independent of port location. Using Eldred’s method, the table below compares the Wray superchargers to their contemporaries:

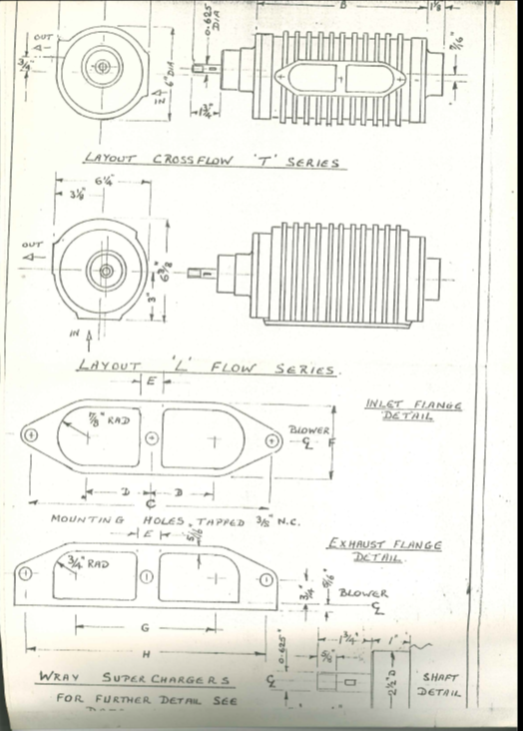

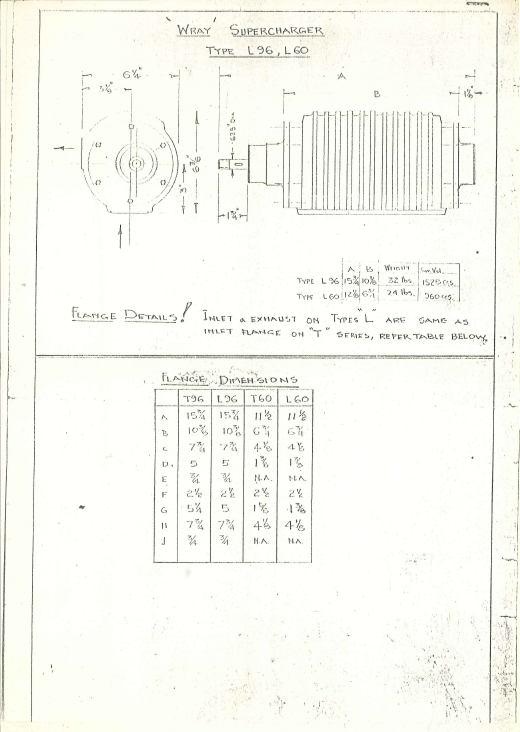

Both Wray supercharger sizes were available with the inlet and outlet port 180º apart (the “T” model) or 270º apart (the “L” model), giving a total of four variants – L60, T60, L96 and T96. Whilst the literature shown later in this anecdote indicates a T60 being made, it is not certain that this ever eventuated.

The L superchargers allow a more compact design, allowing installation between the engine block and the firewall of BMC vehicles. The supercharger was bolted directly to the cylinder head, the inlet manifold ran across the bottom of the casing, extending past the end plate. A downdraft carburettor was located next to the end plate between the engine block and the firewall. The larger supercharger casings were produced in two models: the first with the same design porting (90º) as the smaller superchargers, and the second with a cross-flow (180º) porting. The variations were achieved by utilizing an internal chamber (in the casting) between the liner and the outlet port. The liner porting was the same for both models.

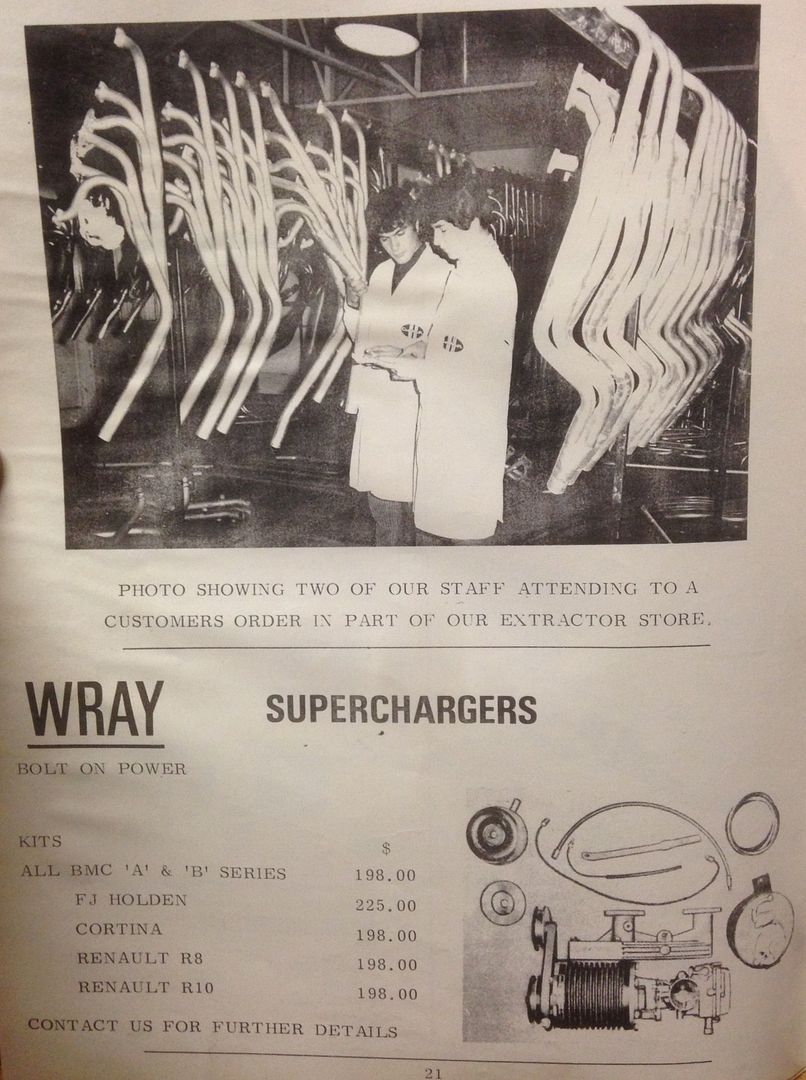

The small L60 and T60 superchargers were originally marketed and sold in kit form for the various BMC ‘A’ and ‘B’ engines (including Minis), &*#@ Cortina 1.2-1.6L four cylinder engines and Renault R8/R10 956cc-1289cc models. The larger L96 and T96 superchargers targeted the 132.5-138ci Holden grey engine. Over the years the superchargers were sold and put to use on numerous applications ranging from 750cc motorcycle engines through to the 202ci Holden red engine.

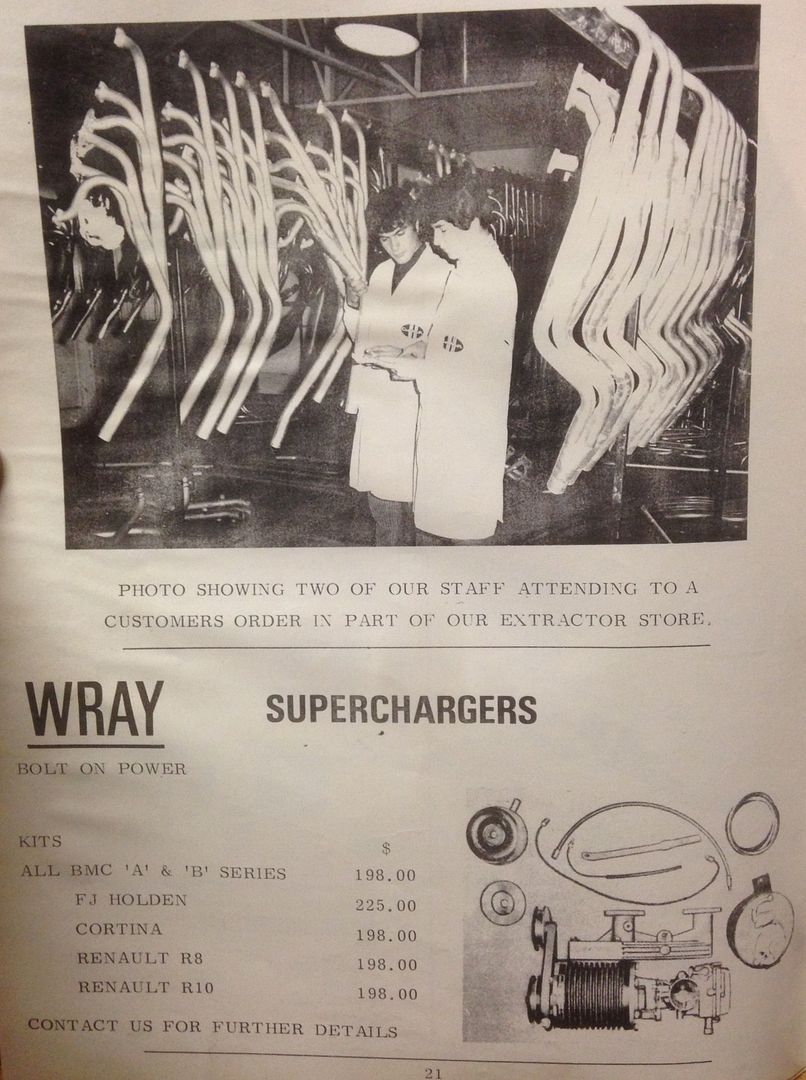

The image shown below is taken from the 1968 Aunger Speed Equipment Retail and Mail Order Catalogue, and shows some of the Wray kits offered. It is a little cheeky… the image to the bottom right is a Judson supercharger kit and Holley carburettor to suit an Austin Healey Sprite.

The image below shows both the larger and smaller Wray superchargers (photo: Fred Radman). Note the absence of the T60 supercharger in the image… it may never have been made by J.G. Wray.

Some Wray superchargers were stamped with serial numbers, including the first one (Mike McInerney, who test-piloted it, can remember John Wray stamping the machine). However, the process was not systematic – none of the those manufactured during Greg’s time at Wray Engineering were numbered, nor any that returned for maintenance.

The newspaper clipping below is from Adelaide’s The Advertiser of Tuesday, February 7th 1967:

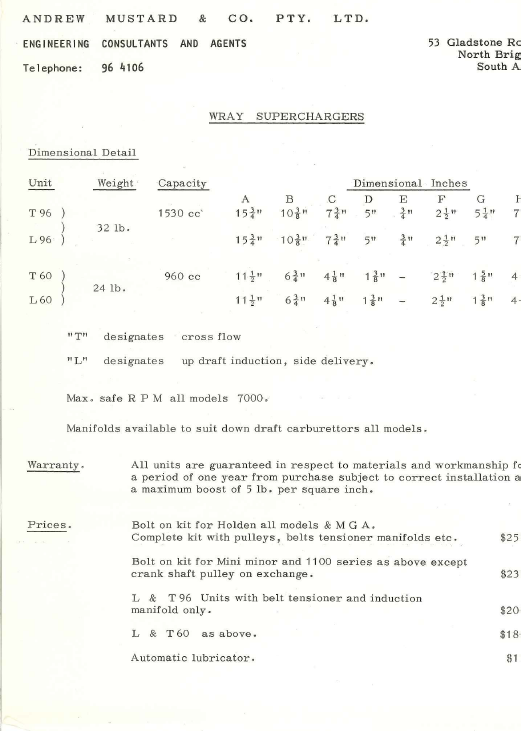

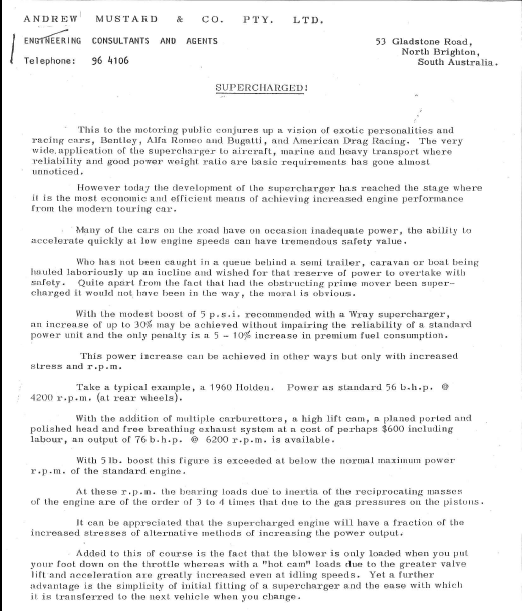

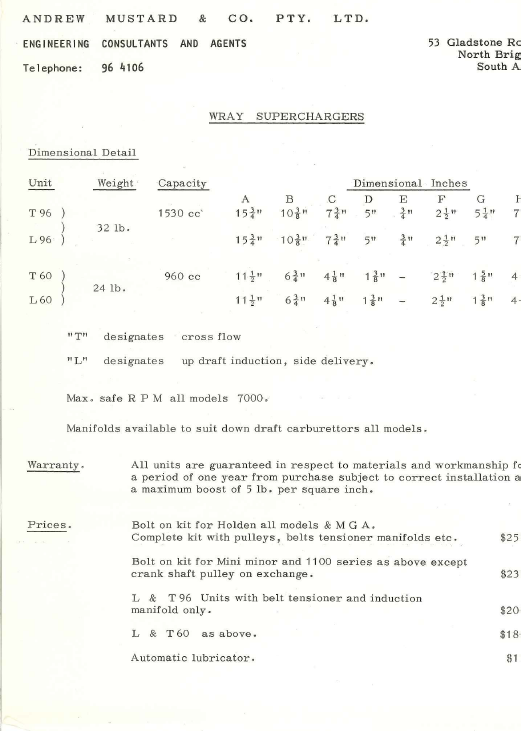

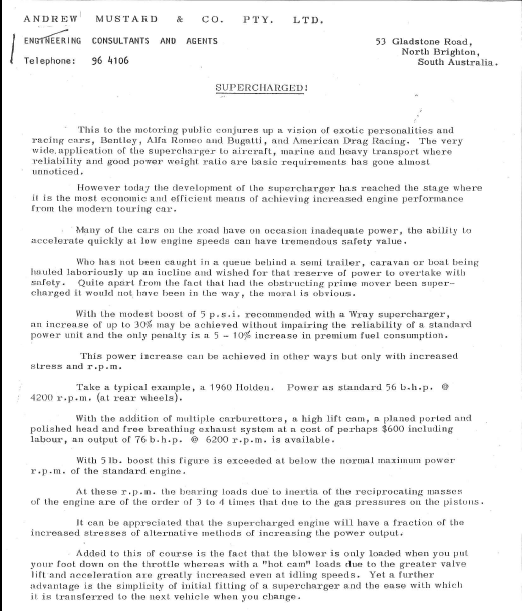

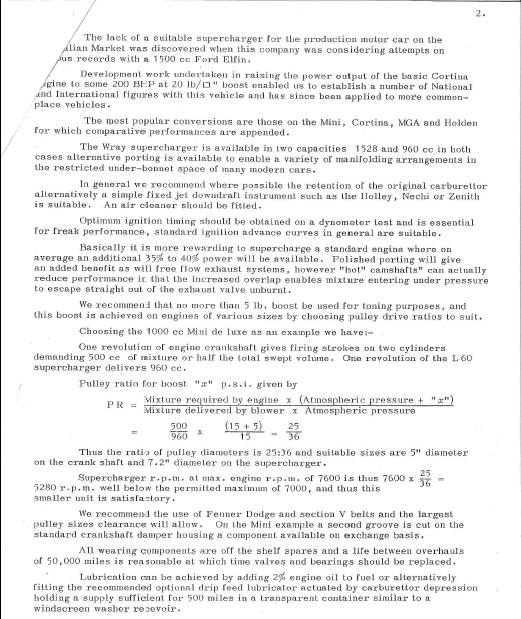

Interestingly, Andrew Mustard was a sales agent for Wray. From my earlier anecdote, Mustard was involved in the Bluebird land speed trials, and owned the Norman-blown Elfin which still holds Australian land speed records. The Elfin, and those records, get a mention in the sales literature below, which I have drawn from Fred’s collection:

It is interesting that Mustard describes phenomena that still apply today – the lower engine stress associated with supercharging, and the effect of valve overlap on boost.

Most of the Wray superchargers were installed by the purchasers, while a few custom installations were done at the factory.

3. Wray Supercharger Construction

John Wray designed and made all of the drawings, timber patterns, tooling and jigs for the Wray superchargers. The pattern for the L96 is shown below (photo: Fred Radman).

The main castings were cast elsewhere, while the machining and assembly was all completed in the engineering factory. With the move from Glenelg to Somerton Park a privately owned foundry was located at the rear of the property, and they provided the castings.

Early Wray superchargers were manufactured with cast iron liners, which were machined and honed. The liners were changed to a seamless steel design which reduced previous issues with liners cracking and/or breaking (we’ll hear more about one such event later). The steel liners were not treated or honed. The liner shown below (photos: Fred Radman) is an early one. The ports (oval slots) are parallel to the casing, and were referred to by Wray as Mark 1 porting. Norman superchargers have similar parallel porting.

The steel pointer in the Fred’s photo below is indicating the wear in the bridge pieces between the oval ports (inlet side).

Later Wray liners had Mark 2 diagonal porting, which imparted a wiping action to alleviate the wear. Judson superchargers used a diamond shaped port for similar reasons. The Mark 2 porting can be seen by the diagonal bridges in the photo below (photo: Fred Radman):

The early model Wray superchargers had a cast aluminium rotor. Due to a lack of quality control at the foundry these rotors had porosity in the castings, which caused a lack of strength. They occasionally exploded at high speed…. and sometimes at not so high speed too.

The photograph above (photo: Fred Radman) shows an early supercharger owned by Fred Radman (we’ll meet him later in this anecdote), complete with cast rotor. The supercharger later split a rotor, though after cutting the drive belt the car was able to be driven home. With the end plate off there was visible wear to the vane slots, with the ends starting to flare out. The split rotor is shown in Fred’s photo below - the crack originated at the corner of the slot, which is a stress riser:

In about 1970 the cast rotors were no longer produced, and instead aluminium billet extrusions were used. This reduced the frequency of rotor failures, though is no guarantee – some of the later rotors have cracked. The photo below, from John Bowles, shows a later rotor with a crack under the black “C” mark:

The rotor drive shafts were generally of a standard length. Custom orders were catered for with longer shafts and drive plate end castings with longer snouts to support the longer drive shafts. Wray supercharger rotors employ four vanes made from fibre reinforced Tufnol (Tufnol, like Bakelite, is a cotton reinforced phenolic resin). The vanes were cut to a rough size, then ground to final size (length, width and thickness) on a tool and cutter grinder. No springs or grooves were used with the vanes. The photo below, from Fred Radman, shows the vane profile:

Lachlan Kinnear remembers a discussion with Alec Rowe quite a few years ago. The conversation discussed the first Norman superchargers, and how Eldred had found a Judson supercharger. Apparently Eldred measured the critical dimensions to make the initial Normans. Whilst the Wray rotor dimensions are similar to Norman and Judson superchargers, they are not identical. The measurements may have been changed slightly by Eldred, or may have been scaled from photographs. Dimensions for the Judsons, Wrays and a range of Normans are shown below:

The Wray supercharger drive end was fitted with two 6303 sealed single race ball bearings and a spacer sleeve retained with a circlip. The non-drive end used one 6303 bearing retained with a circlip and a welsh-plug end cover. Note that this is similar to a Judson (which uses a single 6203 ball bearing at each end of the rotor), but different to a Norman, which has a single race ball bearing at the drive end and a roller bearing at the non-drive end, which slips the inner and outer races to allow the rotor to grow under heat. The Wray, like the Norman, uses a single lip seal (TC12420 for the Wray, with the Normans using a variety of seals) to seal the drive end. The Judson is different, using two seals on the drive end and a single seal on the non-drive end.

The Wray supercharger cast end plates were machined in a lathe. The clearance between the rotor and the drive end plate was set and the non-drive end clearance governed by the expansion of the rotor and housing. The expansion of the alloy rotor and the housing was similar and if the initial manufactured clearances were correct there were never any issues of seizing. This again is different to the early Normans, where there is significant difference in the growth of the steel rotors and alloy casings.

Wray Engineering manufactured various cast aluminium manifolds which were supplied with the ‘kits’ and these along with other designs were also available to customers to assist with other variations for individual installations. Otherwise, fabricated steel manifolds were easy to manufacture. The ‘kits’ did not have relief valves, though many of the later custom installations incorporated the valves, which were manufactured in the workshop. The image below (photo: Fred Radman) shows the T96 intake manifold. Note that the same casting is used for a single-barrel downdraft carburettor (the upper image), or a sidedraught carburettor (the lower image). The sidedraught option is effected by cutting the casting off at the flange. The pattern was originally made to suit the downdraught carburettor and then was modified at a later stage

Two-stroke oil was generally added to the petrol in the fuel tank for lubrication. Some customers added ‘oil injectors’ (like the Marvel Mystery Oiler used in Judson superchargers) to the inlet manifold to negate the need for premixing oil/petrol in the fuel tank. Typical Marvel oilers are shown below (photo: Fred Radman). Water injection was also used in some installations.

Various carburettors could be used; the preferred choice for later Holden installations being a 2” SU carburettor and a downdraught for the BMC kits. Manifolds could generally be machined or modified to suit various choices of carburettor. The photo below shows a T96 supercharger with a Weber DCOE adaptor, whilst the second image shows a fabricated Weber DCOE to L60 adaptor (photos: Fred Radman):

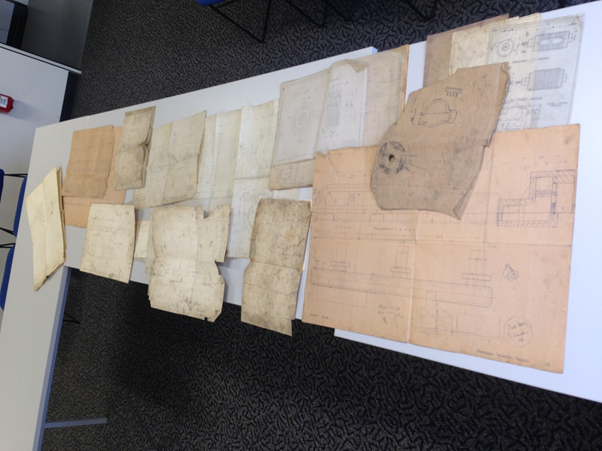

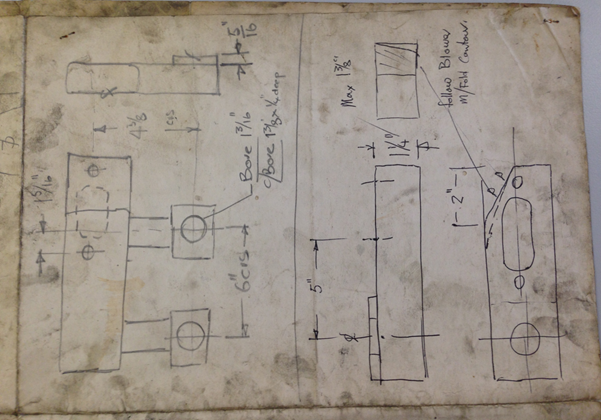

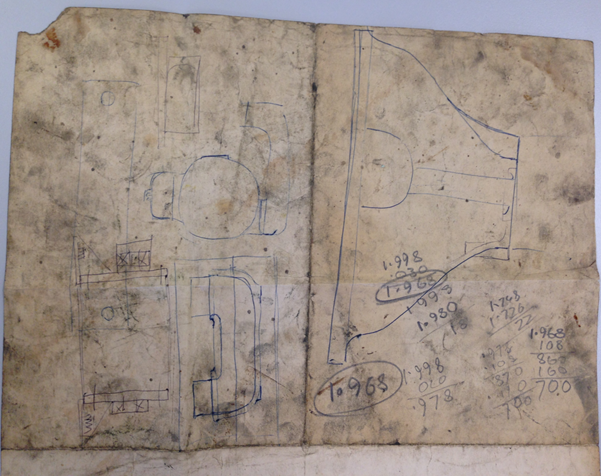

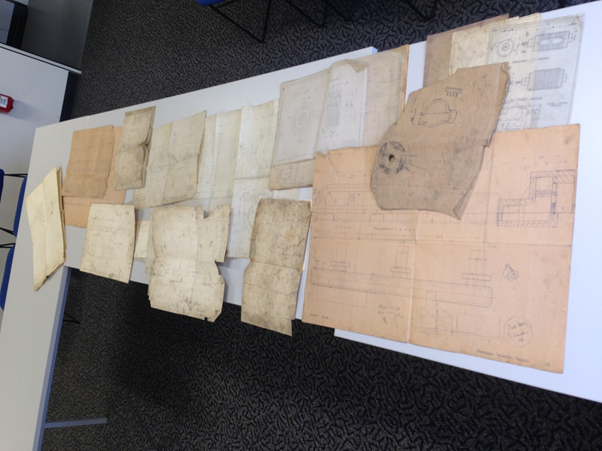

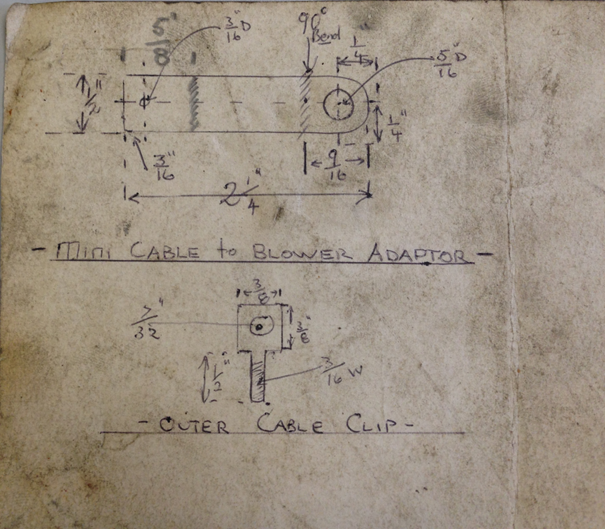

The engineering drawings below come from Fred’s collection:

4. Wray-blown Vehicles

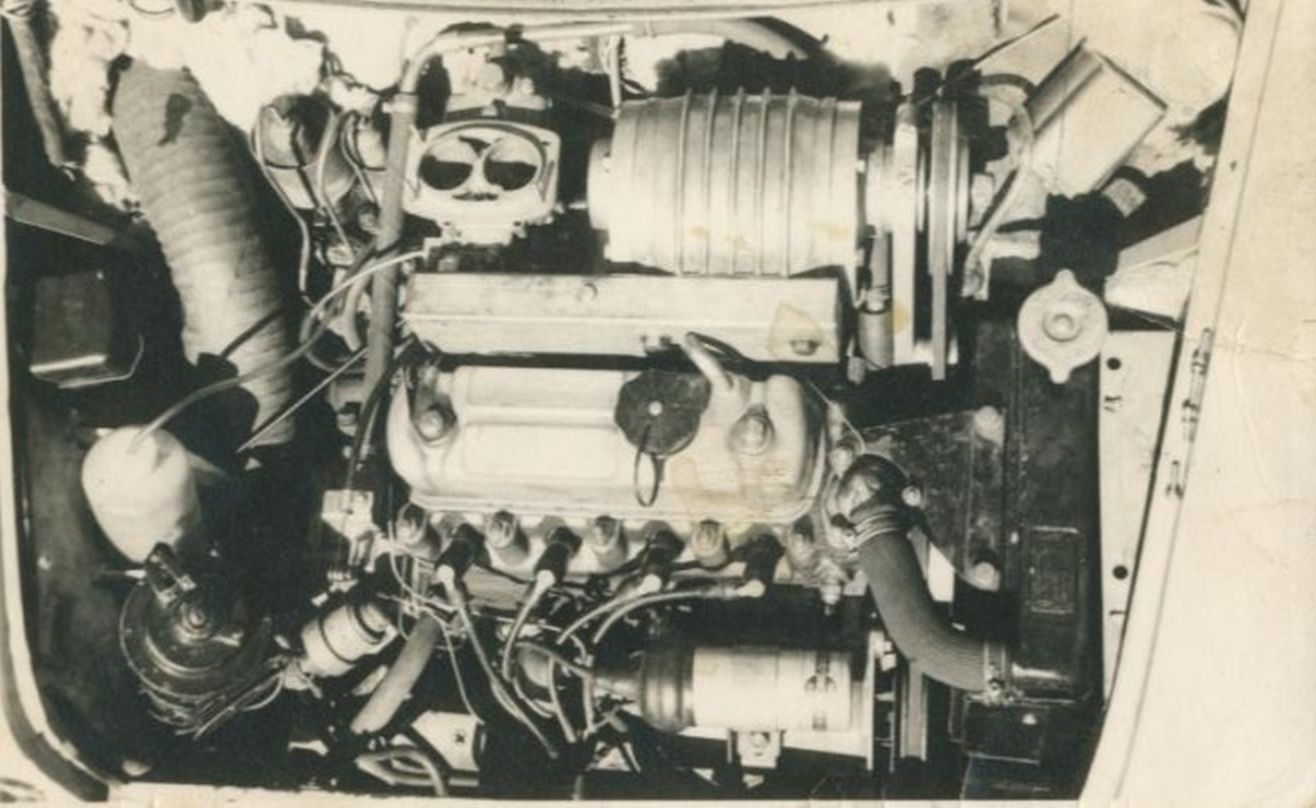

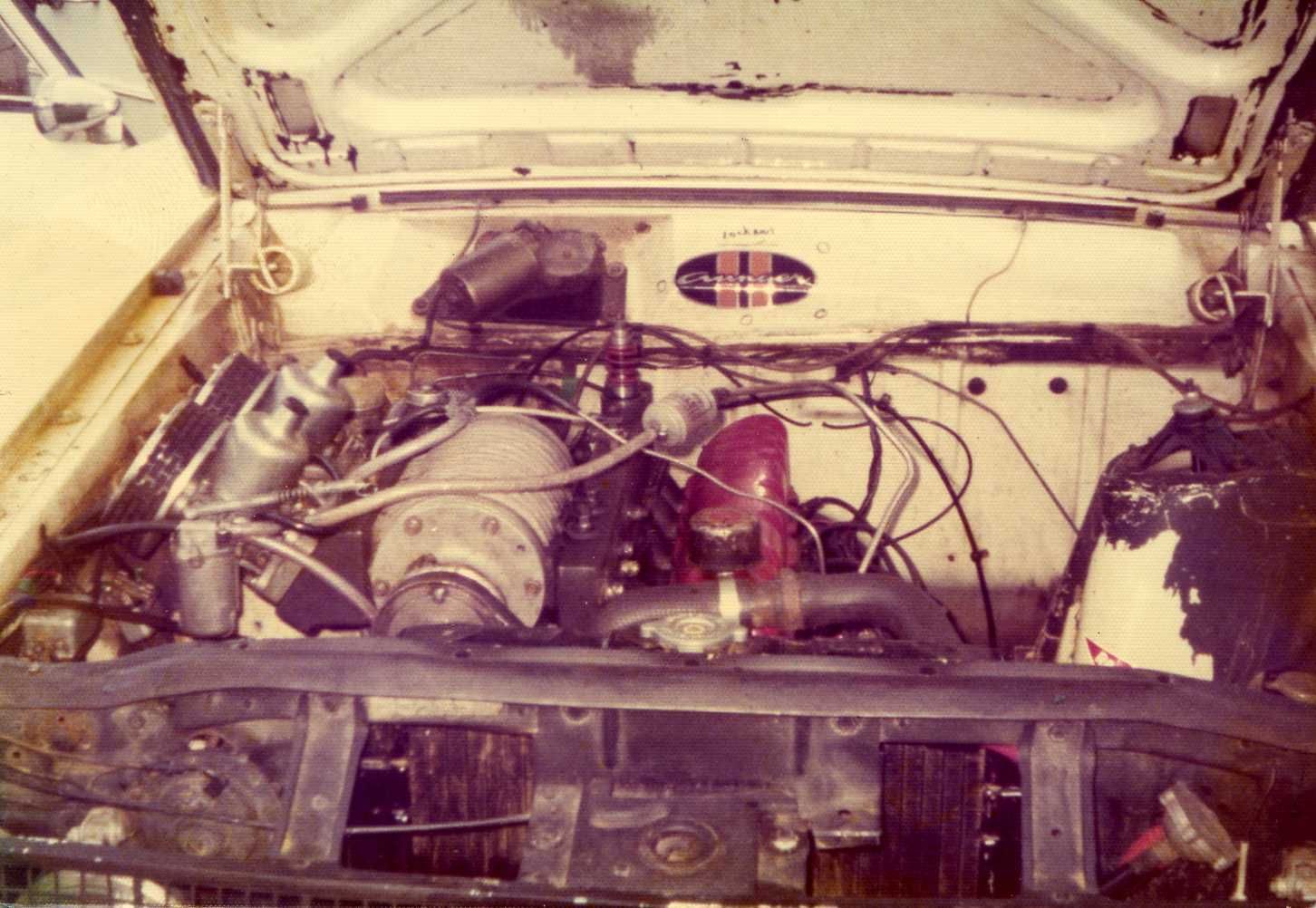

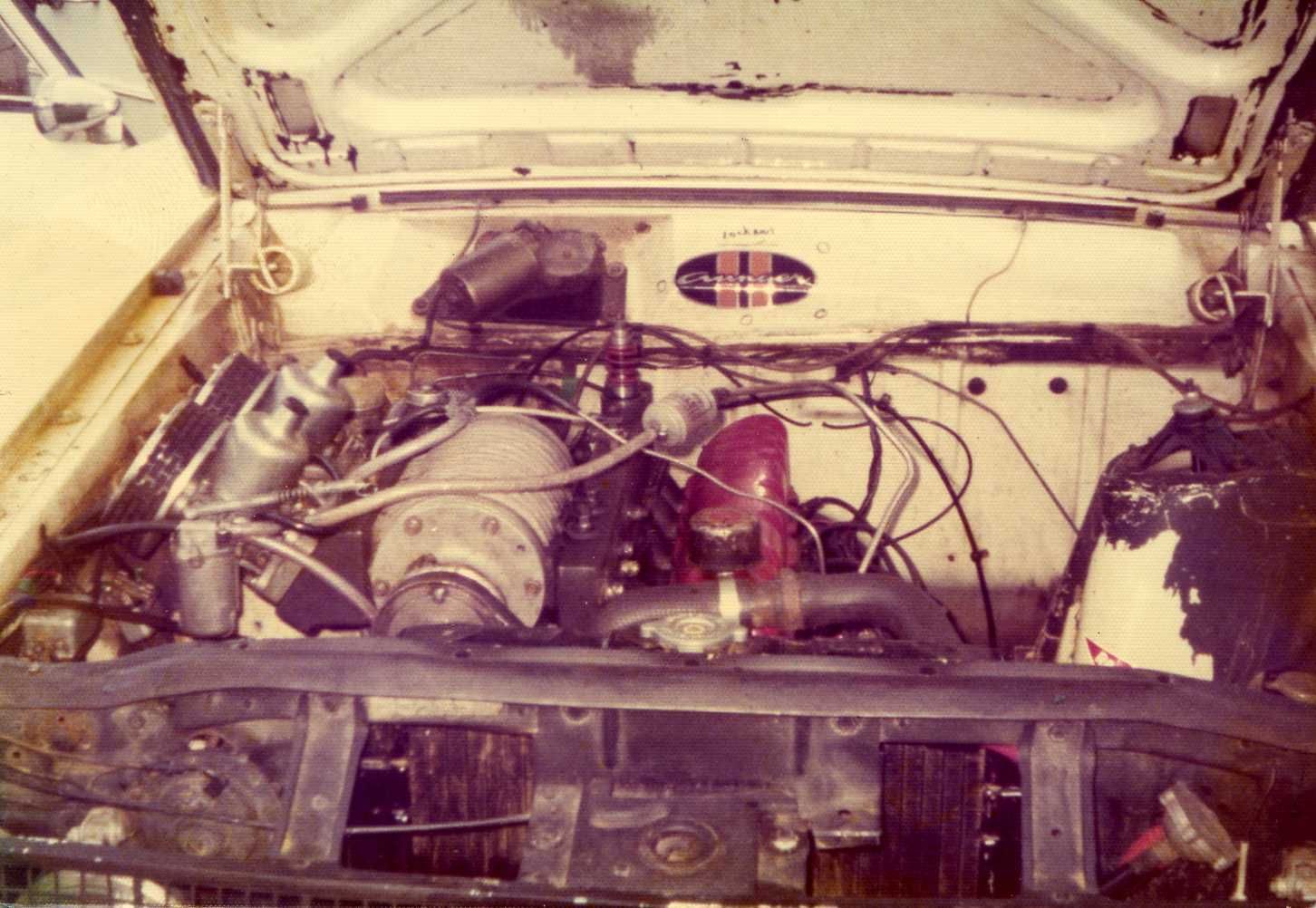

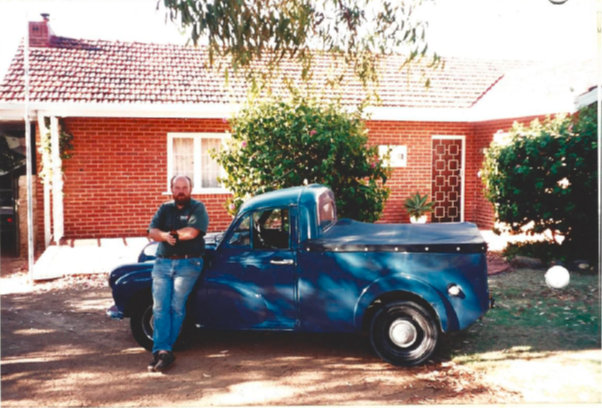

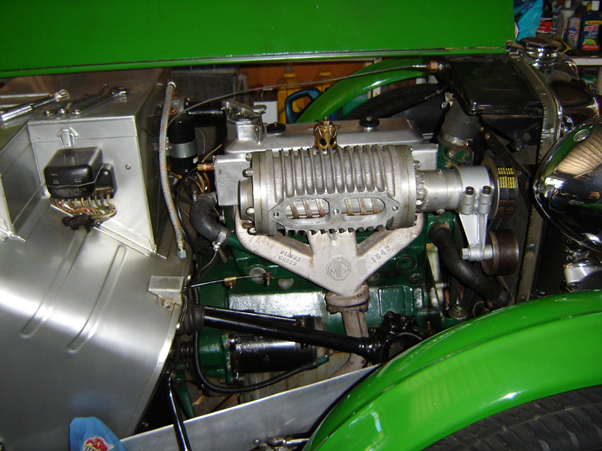

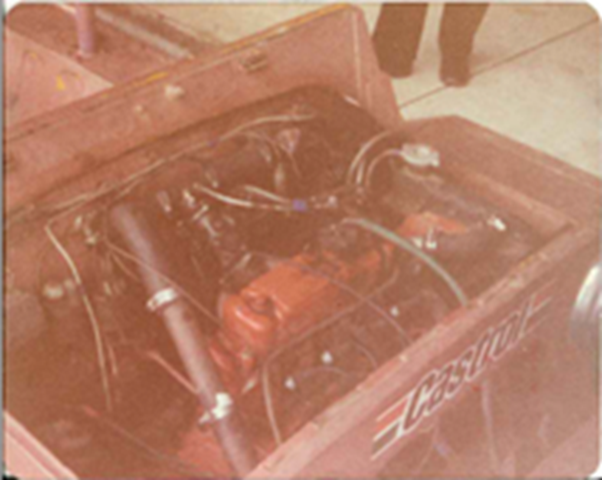

Wray superchargers were fitted on a very wide range of vehicles. The first was Mike McInerney’s FJ, shown below.

The FJ was Mike’s first car, an ex-Department of Supply 132.5ci FJ Holden utility (in Maralinga Gray colour) which he bought at auction in 1960 for £165. The Department of Supply was an Australian government department that existed between March 1950 and June 1974, and managed aluminium production, tin import, control of atomic energy materials, supply of war material, building and repair of merchant ships and promotion and production of liquid fuels. Mike used the vehicle for milk-rounds from 1962 through 1965. In 1965, with the Wray works still operating from Glenelg, Mike fitted the first prototype large Wray supercharger. An adjustable oil injector was used to provide lubrication, with the bottle mounted on the scuttle. A sight glass was fitted to the injector to show the flow of straight 30- weight engine oil. Mike milled the head to take Holden 179ci red motor stellite valves (10% larger on the inlet and 5% on the exhaust than the standard grey) and lowered the compression ratio. Mike also milled and fitted main bearing cap bridges to the crank. The three-speed crashbox had a floor shift built by Alex Rowe (a joy to double clutch), 11” disc brakes on the front (a NSW-based company made them to fit onto the standard FJ Holden 15" wheel hubs), Dunlop R5 racing tyres, and ladder braces to strengthen the subframe to the chassis rails. The engine could pull from 10mph through to a top speed of about 90 mph in top gear, was very quick off the lights and very flexible throughout the rev range. The engine did not have a ‘big’ camshaft. It had a sign on the back, opposite the number plate – “Supercharged by Wray”… reminiscent of the “Supercharged by Norman” emblems of the era.

Mike did not have a relief valve fitted between the supercharger and the cylinder head, giving no overpressure protection in the event of a blower bang. Following a bang in Mildura, the blower cracked the cast iron liner bridges which act like a grille across the supercharger discharge port. The bridge pieces ended up in #6 cylinder of the grey motor. Mike disconnected the blower belt and drove back to Adelaide at low speed (some 400km…). On pull down of the grey, there was a damaged #6 piston and some hammer damage to the valves and valve seats. On tear down of the blower, it was noted that the rotor vane slots were wearing. The supercharger was rebuilt using a tougher alloy for the rotor and the casing liner was engineered from bore casing steel. The sleeve was pinned using a dowel with the front end plate as the locator. It was decided to follow the wisdom of Alex Rowe and mix two-stroke oil (about 2-2.5%) with main fuel for vane lubrication. The oil injector was deleted, and a relief valve installed. Mike took the ute to Darwin in August of 1968 and sold her in December 1969 to buy a brand new 1969 Holden V8 4-speed ute.

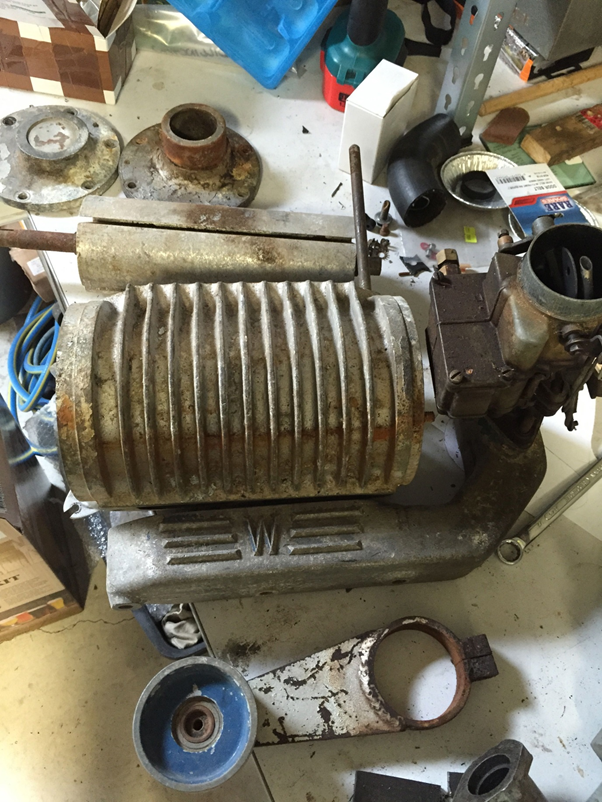

The photo below is of the Wray fitted to Mike’s FJ, running a single grey motor Stromberg carburettor (photo: Mike McInerney).

Note the “W” and fins cast into the inlet manifold.

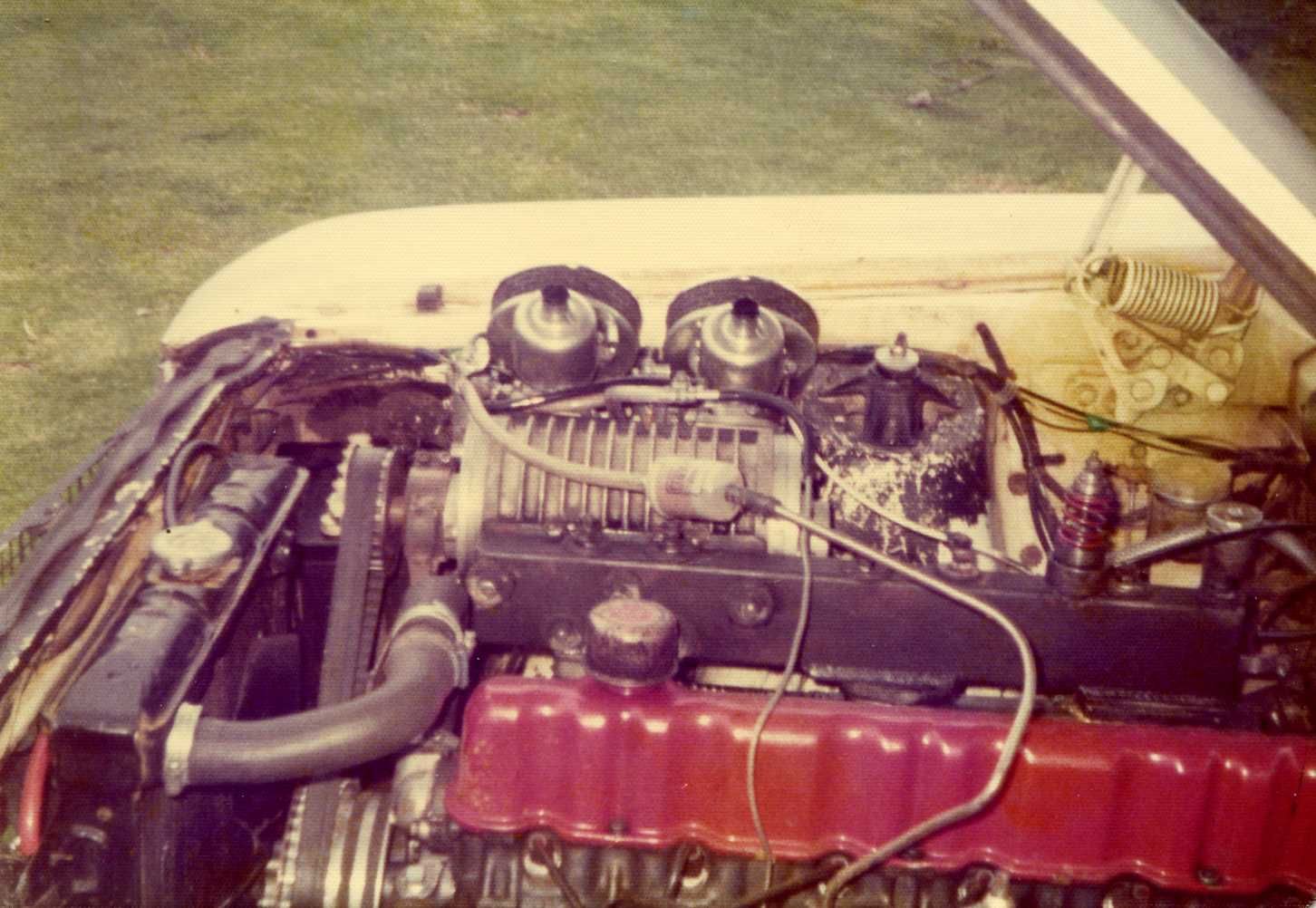

A few months after Mike supercharged the FJ, Ian Robinson (Ronnie) installed the smaller model Wray supercharger on his street-driven 1310cc Mini Cooper S. The Mini is shown below:

The photo below shows the interior of the Cooper… with a suspicious looking boost gauge on the far right hand side of the cluster .

The Mini’s engine is shown below.

Robbie had bought the Mini new, having to wait twentyone weeks for the vehicle to be imported from the UK. The car was the 6th in South Australia. Robbie had a penchant for speed, with the brand new (and as yet naturally aspirated) Mini clocking some 90mph down Pirie Street, Adelaide in the early hours of his first day of ownership.

On fitting the supercharger, the car was found to run hot. A second radiator was installed in what was becoming a very cramped engine bay. The twin down-draught carb shown in the photo above would later be replaced with an 1¾” SU from a Jaguar. The SU’s needles were turned down on a lathe to suit the increased fuel load. The Mini was fed a diet of 115 octane fuel from BP, along with upper cylinder head lubricant added to the tank. A decompression plate was manufactured from 1/8” steel plate, with XW Falcon pushrods being used to bridge the increased distance.

The Wray-blown brick was quite a weapon… Robbie would own the machine for three years, and only hold his license for a few months in that time. The locals would pause in sipping their pints at the local hotel as the Mini spun 360º on it’s way past from the train station. A journey from Adelaide to Mildura (some 400km) was completed by the brick in 3¼ hours… the 75mph (120km/h) average speed probably had something to do with the empty fuel tank five miles from the journey’s end.

The local Police were equipped with Valiants, with Robbie keeping them busy. One journey over the ranges had the Mini clocked at 130mph, followed by 115mph past the local shopping centre. Slowing down over the railway tracks, Robbie made a wrong turn and ended up in a dead-end. The Valiant, in hot pursuit, was not as agile as the Mini and failed to negotiate the last corner. The Police, climbing from the damaged Valiant, were none too amused, and decided Robbie would probably be better off walking for the next 5½ months.

On getting his license back, some testing was in order. A large model Wray had been fitted to a bloke’s white Mark 1 Cortina GT. This engine was a five-bearing 1500cc with four-speed gearbox. The Corty was almost too hairy to drive, easily breaking traction in first gear, especially if the road was wet. The “test run” between the Cortina and Mini in the local hills got a little out of hand, with the Cortina ending up on it’s roof on the train tracks. Robbie would be walking for another two years two months after that drive.

Robbie’s wife also pushed the car hard. Refuelling the car at the local service station, the attendant refused to add upper cylinder head lubricant to the tank. A phone call had to be made to Robbie to prove that his wife was correct. When the tank was full (with the required lubricant too), the Mini departed at some speed… leaving black tracks for quite some distance down the street. Another incident saw the Mini clocked by amphometer at some 75mph in a 30mph zone. This also didn’t impress the local Police (though the “Unmarked Police Car” sticker on the rear window may have had something to do with that).

Sadly, the Mini was eventually written off.

Robbie can also remember a Datsun 1600 that received a Wray supercharger. The car was used to impress potential customers. On launching the Wray-blown Datto, non-believers would be asked to open the doors on the moving car. The supercharged engine torqued the body so much that the doors could not be opened.

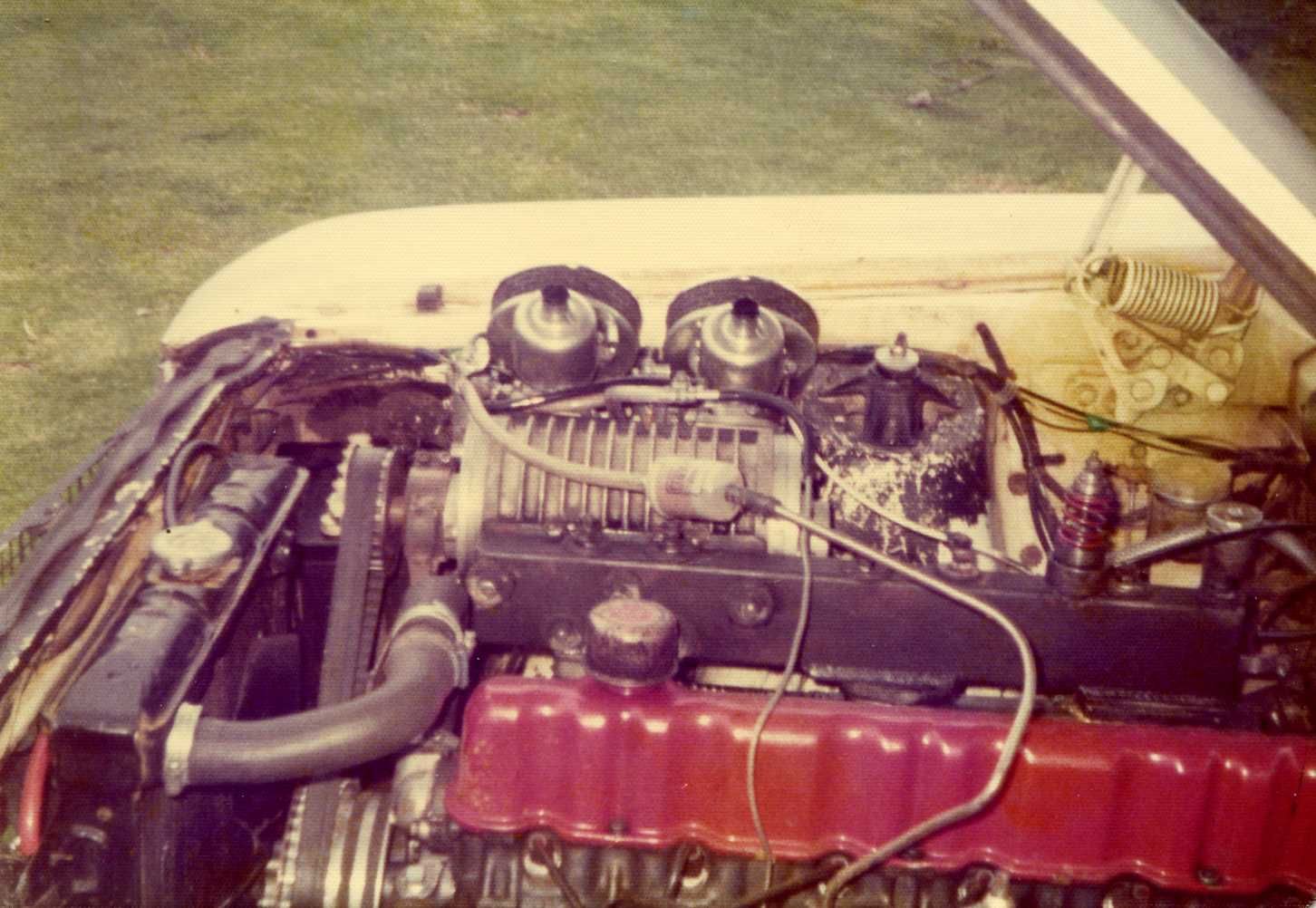

Greg Pill built a Wray-blown XR &*#@ Falcon stationwagon, shown in the images below (from Greg):

Greg’s Falcon ran the 170ci Pursuit straight-six engine, which was available from 1961-1972 (XK, XL, XM, XP and XR Falcons), and was good for up to 111BHP in naturally aspirated form. Greg’s 170 used short deck height pistons to lower the compression to 8.25:1, a worked cam, extractors and a ported and polished head. Two additional mounting plates were welded to the cast head which provided three ports. Greg utilised the larger of the Wray superchargers, mounting it via a box manifold with mounting bolts passing through the pressure envelope and sealed with rubber washers. The supercharger was fed by twin 1¾” HD SUs with the angled main body (the inlet manifold mounting face is equally angled to ensure the float bowl orientation is level). A double v-belt from the crank drove the water pump and alternator. The water pump pulley was machined to suit a gilmer belt which then drove the supercharger. A little unorthodox, but a smart way to solve the problem of fitting everything within the confines on the right side of the motor. A relief valve was fitted to the top rear of inlet manifold. The Wray delivered some 14psi of boost, and was street driven and never raced. Greg sold the &*#@ without the supercharger.

Following on from my Eldred Norman anecdote, I got to thinking about the period in Australia’s automotive history. The 1950’s and 1960’s were a period where we still relied heavily on local product – the market flooding of readily available imported go-fast parts for the small block Chev had yet to occur. This need for local equipment spurred on some very cool Australian engineering, including Eldred’s work. In the local forced induction field, there were numerous people bolting on (or making kits for) imported superchargers. This is a phenomena we see today with both Harrop (who kit out the Eaton TVS machines), the Castlemaine Rod Shop (who kit out the Aisin SC14 machine), and Yella Terra (who kit out the Eaton M90). Sprintex are perhaps the only Australian company who manufacture their own (twin screw) machines.

What is interesting (and also rather cool) is that Eldred was not the only Australian who was manufacturing superchargers (and not just kits) in the 1950’s and 1960’s period. One of Eldred’s contemporaries, competitors, and fellow South Australian was John G. Wray. The anecdote below tries to paint a picture of the Wray supercharger history. Just like my Eldred Norman anecdote, a word of warning regarding the information below. Some of the people who witnessed the events below have sadly passed away, including John Wray. It has also been half a century since the Wray supercharger was conceived. This anecdote has been written drawing together information from a broad variety of sources, many of whom are trying to remember events of fifty years ago. There may be inconsistencies with the information, or outright errors. Caveat emptor. I also owe a debt of thanks to a great number of people who helped pulled together the pieces of the “patchwork quilt” that became my Wray anecdote.

1. J.G. Wray

John Graham Wray was born in 1930, at an unknown location, in Australia. John married, and he and his wife Margaret did not have children. John spent some of his early years in England with his wife on a working holiday. His interest there was in automotive engineering and sporting cars. On return to Australia John was working as a Castrol sales representative, with Margaret working as a nurse. Over time John accumulated quite a few engineering tools and machines. He eventually started a small engineering shop (J.G. Wray General & Maintenance Engineering) at Newman Lane Glenelg, South Australia. The shop catered for general and maintenance engineering with John and staff being involved with the following activities:

• Small production runs of components for machinery,

• Design, manufacture and maintenance of machinery for the testing and manufacturing of automotive components,

• Design, manufacture and maintenance of machinery for the textile industry,

• Manufacture of marine components,

• Manufacture and maintenance of mining equipment, and

• Jobbing and ‘one off’ work.

Wray Engineering raised patents for example on a “burr beater” agricultural implement.

John owned a white hardtop MGA 1558cc twin-cam that he either brought back from or imported from the UK. He later sold the MGA to purchase an Alpha Romeo GTA. John’s main interest at that time was with yachts, bringing with that interest numerous customers to the company with the manufacture and development of marine parts and marine maintenance. John constructed a 30ft double-ended fibreglass ocean going yacht in one of the workshop bays. He used the yacht for many years until health issues forced him to sell it. His other interest in later years was exploring outback Australia in his 4WD. John passed away about eight years ago in Adelaide. The following article is drawn from the (Adelaide) Advertiser of the 14th of October 1954:

Vintage Racing Car Has History

Historic Racer

A vintage racing car, now being rebuilt in South Australia, has one of the most colourful histories of any vehicle in this State, and because of its age an even more colourful one than the ex-Prince Birabongse, MG K3, owned by Andy Brown. The car is a 1923 2-litre Miller, owned by Gordon Haviland, and at present being rebuilt by John Wray and Len Poultridge. Believed to be the first Miller to leave America, the car was taken to Europe in 1923 with two other Millers to compete in under 2-litre formula races. Count Louis Zborowski took delivery of the first car and entered it in the Spanish Grand Prix, run at Sitges-Terramar, in which he finished second. The other Millers also ran against Zborowski in the Grand Prix de l’Europe, at Monza, one of them, driven by Murphy, scoring third position. Count Zborowski kept his car when the other two returned to the US, and raced it in late 1923 and early 1924 before competing in the 1924 French Grand Prix. Well known author and writer in 'Autocar,' S. C. H. Davis was Zborowski's mechanic on this occasion. The introduction of the supercharger on other vehicles gave the Miller a considerable disadvantage in this event, but when 'blowers' were fitted, an American driver, Harry Hartz, covered 50 miles at 135 m.p.h in 1925. The Miller did not finish in the French Grand Prix, and Count Zborowski was killed at Monza shortly afterwards when his Mercedes skidded into a tree during the running of the Italian Grand Prix. All Zborowski's cars were then sold. The car was bought by Dan Higgen and raced at Southport Sands, in England in 1925. The Miller covered the flying kilometre in 25 seconds, and finished fourth. It raced in several events at Brooklands and in other meetings during 1925 and 1926. The car came to Australia a year or so later. It has had several owners in this country and competed in numerous hill climb and other events. The body has been lowered, but it still retains its original Miller engine. Picture shows John Wray working on the car this week.

A South Australian with a passion for old race vehicles who goes on to build his own superchargers? Sounds like another gentleman we have met before . As an aside, Count Zborowski built and raced the original Chitty Chitty Bang Bang… with a 23-litre Maybach aero engine (!). The Miller 122 shown in the photograph above is centrifugally supercharged.

Wray superchargers were manufactured at the Glenelg factory up until about 1967. The company moved to larger premises at nearby 46 Byre Avenue, Somerton Park in 1970 (now home to Tintworks window tinting), where production continued until about 1983. The image below, lifted from the internet, shows the Somerton Park facility in 2009, which is very similar to how it looked in the early 1980s.

John Wray’s direct involvement in the manufacture of the superchargers continued until about 1974. Wray superchargers manufactured after that time were still made at Wray Engineering, but manufactured by staff after hours and on weekends, with little to no advice from John. Batches of superchargers would be made, and sold to speed shops. It is estimated that around fifty superchargers were built in this fashion. Whilst quite a few people were employed at the Wray works, a few were heavily involved in the supercharger side of the business. James (Robbie) Robinson started at the Glenelg workshop and moved to Somerton Park. He was a leading hand until he left about the mid 1970’s. Greg Pill started as an apprentice in 1970 and worked there until 1985, having been a leading hand for about nine years. Robert (Bob) Cronin worked as a machinist from about 1975 until 1983. We will hear more about Robbie, Greg and Bob (and their vehicles) later in this anecdote.

2. Wray Supercharger Models

Like the Norman and Judson superchargers, the Wray supercharger was a sliding vane unit operating at relatively low pressure (~5psi boost). Like the Judson, and unlike some Normans, all Wray supercharger casings are 100% air-cooled. Wray offered two sizes, the smaller having a displacement of 60ci/rev (960cc) and the larger a displacement of 96ci/rev (1530cc). Note that these capacities of swept volume are calculated using the “modern” method of measuring them. In the example drawing below this means work out the volume shown in red, and multiplying it by six (yes, yes, I know, the Wray has four vanes… . it’s just an example ).